The Mystery of the Strong Euro

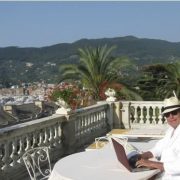

I sit here on the Carrera marble paved terrace of the Emperor?s Suite of the Imperial Hotel, in Santa Margherita Ligure on the Italian Riviera. As the sun sets into a languid Mediterranean, a distant church bell tolls, calling the evening mass. A flock of larks perform a spectacular aerobatic display overhead. A never-ending torrent of Vespa?s speed past on the road below, driven by texting cigarette smoking young women, like a swarm of angry wasps.

A plaque on the wall tells me that the peace treaty that ended WWI between Germany and Russia was negotiated in my bedroom in 1922. At night, I count no less than 22 goddesses, nymphs, and cherubs gazing down on me from the fresco above. It seems that the hotel was once a summer palace for some long forgotten European nobility. Offshore, the mega yachts of Russian oligarchs bob at anchor, drifting with the tide, our visiting nouveau nobility.

All of which leads me to ponder the question of the day: ?Why is all of this so damn expensive?

Dinner down at the market corner trattoria is costing me $100, and it rises to $200 or $300 for the nicer places. A five-minute taxi ride set me back $20. Even a lowly, genetically engineered Big Mac here costs $5.

It?s not like our continental cousins are rolling in cash these days. Now that Japan is on the mend, thanks to Abenomics, Europe has the world?s worst economy. The unemployment rate is 26% in Spain, and 40% for those under 25. Rolling layoffs are hitting the French auto industry, long the last bastion of the protected job. Italy is in its third painful year of recession. Greece is only just getting off its back after a European Central Bank enforced austerity. Chinks are even starting to appear in the armor of the German economy.

The weak economy has fueled non-stop political crises in Spain, Portugal, and Greece. Italy is not even sure it has a government. The debt crisis is never ending. Even European Central Bank president, Mario Draghi, seems to be taking a page out of Ben Bernanke?s playbook. He has recently said that interest rates will remain ?at or below current levels for an extended period.? With all of this angst, you would think that the Euro was the greatest short on the planet.

Except that it isn?t.

So we have to search for he reasons why. The great mystery among economists, politicians, bankers, and hedge fund managers here this summer is why the Euro is so strong, given these desperate fundamentals.

I am now two weeks into making the rounds with the European establishment, and to a man, they are short the beleaguered continental currency in their personal accounts. There are really only two opinions here. One is that the Euro is headed to parity against the dollar, down 24% from here. The other is that it will revisit the old 2002 low of 86 cents, down 32%.

The reality is that while the Fed?s balance sheet continues to expand at a breakneck pace, the ECB?s is shrinking. This is because European banks are repaying the subsidized loans they received at the height of the crisis to shore up their balance sheets. It is a distinctly positive development for the Euro.

Relentless austerity measures have the unanticipated side effect of increasing the continent?s current account surplus. Imports are drying up, further boosting the Euro, much to the grief of China. While the economic news here is bad, it is better than it was a year ago. This is what the year on year precipitous drop in sovereign bond yields is telling you. So there is a huge amount of bad news already in the Euro price.

Global currency positioning may also have something to do with it. This year, the big play was in selling short the yen, Australian and Canadian dollars, and emerging market currencies against the greenback. The Euro is simply benefiting from inertia, or getting ignored.

In the meantime, some big hedge funds have been throwing in the towel on the Euro and shifting capital to greener pastures elsewhere. With all of Europe seemingly competing for my beach chair, who is left to sell the Euro?

In the end, the strength of the Euro may end up becoming one of those ephemeral summer romances. There is no doubt that the American economy is improving, and further distancing itself from Europe.

This will turbocharge that great decider of foreign exchange rates?interest rate differentials. That?s when rising US rates and flat or falling European ones can send the buck in only one direction over the medium term, and that is northward.

Then my European friends should become as rich as Croesus, and the price of that Big Mac will come more into line with the one I buy at home.