An Evening With the Chinese Intelligence Service

The current chip war with China brings back memories of my five-decade-long relationship with the People’s Republic of China.

I normally avoid the diplomatic circuit, as the few non-committal comments and soggy appetizers I get aren’t worth the investment of time.

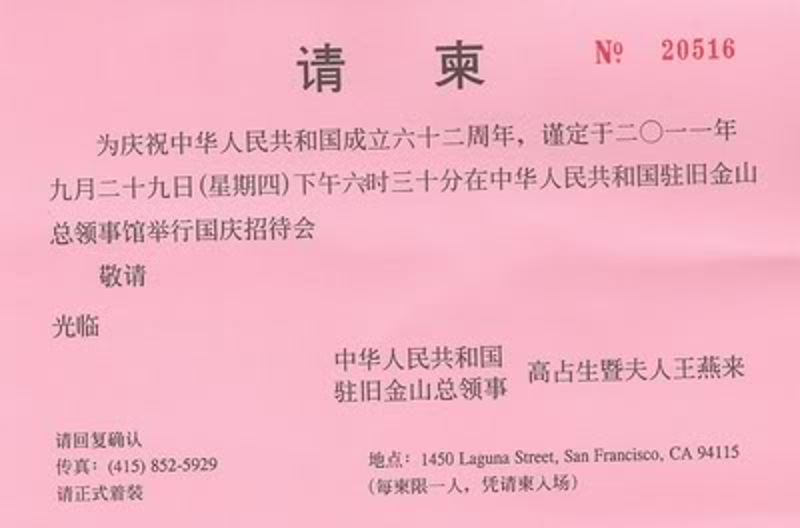

But I jumped at the chance to celebrate the 62nd anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China with San Francisco Consul General Gao Zhansheng.

Happy Birthday, China!

When I casually mention that I survived the Cultural Revolution and interviewed major political figures like Premier Deng Xiaoping, who launched the Middle Kingdom into the modern era, and his predecessor, Zhou Enlai, modern-day Chinese are enthralled. It’s like going to a Fourth of July party and letting drop that I palled around with Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin.

Five minutes into the great hall, I ran into my old friend Wen, who started out her career with the Chinese Intelligence Service and had made the jump to the Foreign Ministry, as all their best people did. She was passing through town with a visiting trade mission.

When I was touring China in the seventies as a guest of the Bank of China, Wen was assigned as my guide and translator, and we kept in touch over the years. I was assigned a bodyguard who doubled as the driver of a tank-like Russian sedan.

The Cultural Revolution was on, and while the major cities were safe, we ran the risk of running into a renegade band of xenophobic Red Guards, with potentially fatal consequences.

I asked Wen when China was going to float the Yuan. She explained that this is something China knew it had to do, but it wasn’t going to be rushed into by some opportunistic foreign politicians.

If it moves too soon, millions will lose jobs, creating political instability, something the central government wants to avoid at all costs. Many of the largest scale employers were only marginally profitable, and a hike in the renminbi of only a few percent would force them out of business. I pointed out that that was exactly what was happening in the US.

Worth More Than Meets the Eye

I warned that if the Middle Kingdom waited too long, Washington would force them into an appreciation through punitive import duties and anti-dumping actions, as we did with Japan 50 years ago.

It was Nixon’s surprise ban on textile imports in 1971 that finally persuaded Japan to float the yen, then at ¥360. If that didn’t convince the Chinese, then imported inflation would. The longer China delays, the bigger the pop when their currency is finally set free.

Wen then went on the offensive, claiming that Chinese workers were being exploited by American companies keeping wages low. The product that China made for $1, and sold to the US for $2, was then sold by Walmart (WMT) for $20, which kept all the profits.

She pointed out that the Walton family had a combined net worth of $238 billion, more than the total worth of the lower 40% of the US population. This could never happen in China.

I told her that by selling the product at $20, Walmart wiped out another US company that used to make that product domestically and sold it for $40, throwing those people out of work.

Modern Times in China

I then asked Wen what were her country’s plans for its massive foreign exchange reserves, now at $3.2 trillion. She agreed that this was a problem because the reserves were pouring in so fast at an embarrassingly high rate of $10 billion a month and that it was the most rapid accumulation of wealth in history (click here for the data). In any case, reserves have been falling for the past year from a peak of $4.1 trillion.

While it had more than enough Treasury bonds, any attempt to sell might cause their value to collapse and freeze relations with the US. I suggested China should start hedging its gigantic holdings without selling them, or some managers would be facing a firing squad in the future.

China tried to recycle its surpluses by buying foreign companies that produce the natural resources it desperately needs. But takeover attempts were fought tooth and nail as a foreign invasion, or on national security grounds, such as the attempt to buy California’s Unocal in 2005 and Australia’s Oz Minerals in 2012.

It was now using a strategy of buying low profile minority stakes in foreign resource companies. China took a big stake in the Petrobras (PBR) secondary equity offering, which didn’t work out so well, as the company is now facing bankruptcy.

I asked her about the real estate bubble in China that was causing so many foreign investors to lose sleep. She said it was true that sales were slow at some luxury buildings in Beijing and Shanghai, but the great majority of developments were aimed at working people and were filling up as soon as they came on the market.

The 40% down payment demanded by the People’s Bank of China headed off the rampant speculation that brought the American financial system down. Buyers of second homes were required to pay entirely in cash.

Rooms With Views

Wen then complained about the aggressive military stance the US was taking towards China, ringing it in with the Seventh Fleet. Holding a knife so close to the country’s foreign supply line jugular vein made them nervous.

China was basically indefensible. All it would take was the sinking of a few grain ships, and 50 million would starve within a year.

Wen told me there is a school of thought in Beijing that as the country’s economic power grows- it passed Japan to become second in GDP in 2010– that the US will increasingly perceive it as a military threat. This would lead America to mete out the same hostile treatment to China as it has done to Russia since the Ukraine War began.

Walking Softly, But Carrying a Big Stick

I assured her that the Seventh Fleet was there to watch and listen, but to do nothing. It was really in a position to provide a security blanket for allies, like Japan and South Korea, but nothing more. China wasn’t engaging in the belligerent behavior that Russia was at the height of the Cold War, like blockading Berlin, basing missiles in Cuba, stationing fast attack nuclear submarines off our coasts, and invading Afghanistan.

I argued that if China truly has no expansionary intentions, the more we know about you, the better. It is always prudent for a potential adversary to conclude you are not a threat, and that no action is needed.

The more you help the US do that, the better. China is decades behind the US in military technology, and you really have nothing we want. Little more than 200 nuclear weapons without an ICBM or submarine delivery systems were hardly viewed as a major threat.

Wen seemed perturbed that I was aware of her country’s nuclear stockpiles, and asked how I knew this. I said that former CIA director Leon Panetta told me. She said “Oh.” I asked what was that test downing of a satellite in space about, anyway. She didn’t answer.

Looking at the world for the next 30 years, who is the Pentagon going to model and war game against, but China, with its 2.5 million-man army?

Wen countered that the People’s Liberation Army was purely a defensive force. With a 12,000-mile land border, an 11,000-mile coastline, and dubious neighbors like Russia, Iran, and India, they have no other choice. Its ability to project force over great distances, as the US can, is virtually nonexistent.

Its 1979 invasion of Vietnam was about reclaiming ten miles of lost territory. China got involved in Korea only after General Douglas MacArthur threatened to rain atomic bombs on the mainland, losing 2 million men, including Chairman Mao’s son. China could have done a lot more in the Vietnam War, but didn’t, limiting its participation to a supply, logistical, and advisory role.

That’s a Lot of Border to Defend

I then warned that if you really are worried about the Pentagon, you should stop hacking into our computers. She replied that the US started this by emptying out Chinese mainframes many times, and they were only responding in kind.

I said yes, but that China was targeting private companies, like Google (GOOG), Microsoft (MSFT), and Oracle (ORCL) that without military-grade software, were unable to defend themselves. The Chinese agencies involved then used the data to their own commercial advantage.

What Did You Say the Password Was Again?

By the time Wen married, China had already adopted its one-child policy. As much as she wanted more children, she understood the government’s need to adopt such a drastic policy. Without it, the population today would be 1.8 billion, not 1.2 billion, and all of the money that went into buying capital goods would have been spent on food imports instead.

The country would have stagnated at its 1980 per capita income of $100/year. There would have been no Chinese economic miracle. She was very proud of her one son, who was a software engineer at Microsoft (MSFT) in Beijing.

Her husband, a mid-level official at the Ministry of Commerce, fared less well, dying of lung cancer at a relatively early age. The US and Europe had exported their worst polluting industries to China to take advantage of lax environmental controls, turning the air in Beijing into a choking haze.

Sometimes her son would come home from school coughing and wheezing so badly that he couldn’t play outside. The two packs of cigarettes a day her husband smoked didn’t help either.

Imported From the USA

I asked if she recalled our first trip together and a dark cloud came over her face. We were touring a section of Fuzhou when three policemen marched up. They started shouting at Wen that we were in a restricted section of the city where foreigners were not allowed. They started mercilessly beating her with clubs.

I was about to intercede when my late wife, Kyoko, let go with a blood-curdling tirade in Japanese that froze them in their tracks. I saw from the fear in their faces that she had ignited their wartime fear of Japanese authority and the dreaded Kempeitai, or secret police, and they beat a hasty retreat.

To this day, I’m not exactly sure what Kyoko said. We took Wen back to our hotel room and bandaged her up, putting ice on the giant goose egg on her head. When I left, I gave her my copy of HG Well’s A Short History of the World, which she treasured, as the book was then banned in China.

Wen mentioned that she was approaching the mandatory retirement age of 60, and soon would be leaving the Foreign Service. I suggested she move to San Francisco, which offered a thriving Chinese community. She laughed. No matter how much prices had fallen, she could never afford anything here on a Chinese civil servant’s salary.

Wen told me that China was grateful for the billions of dollars that foreigners had poured into her country as a result of my writings. I replied that I was simply trying to show my readers where to make some money, nothing more. It was pure opportunistic self-interest.

One of my early recommendations, Chinese search engine Baidu (BIDU), was up more than tenfold in less than two years. Did she happen to know about any more future Baidu’s? Wen said that she wasn’t that close to the stock market, but that she would get back to me.

I asked Wen if she still had the book I gave her nearly five decades ago. She said it had become a family heirloom and was being passed down through the generations. As she smiled, I noticed the faint scar on her eyebrow from that unpleasantness so long ago.

In view of Wen’s comments, I think you have to pass on investing in China (FXI) for the short term.