Back From My 50-Mile Hike

I realized that perhaps I had bitten off too much taking the Boy Scouts on a 50-mile hike one minute into the adventure.

Cutting everything to the bone, I was only able to trim my pack down to 50 pounds. That was with chopping my food ration in half, leaving an extra cell phone battery behind, and bringing only one set of clothes.

However, I had to bring a five-pound first aid kit to care for the 14 scouts, my own tent, and all the maps needed to keep us on course.

Then at the last minute, another five pounds of medical releases, a satellite phone, and an electronic thermometer were dumped on me by worried parents, taking my load up to a bone-breaking 55 pounds.

That’s a lot for a 68-year-old. That’s a lot for anyone.

But then the Desolation Wilderness, the roof of the High Sierras, is one of the most stunningly beautiful places on the planet. All other outdoor trips for the Boy Scouts this year had been cancelled, thanks to the pandemic. And at my age, who knows how many 50-mile hikes I have ahead of me? It was now, or maybe never.

But then the Desolation Wilderness, the roof of the High Sierras, is one of the most stunningly beautiful places on the planet. All other outdoor trips for the Boy Scouts this year had been cancelled thanks to the pandemic. And at my age, who knows how many 50-miles hikes I have ahead of me? It was now, or maybe never.

We took temperatures every morning. All 50 miles were hiked with masks, as did every other group we ran into. Carpooling was banned and every parent had to bring up their own kid to Lake Tahoe. It all worked as no one got sick.

We didn’t do just any 50-mile hike. We attacked one of the toughest in the United States. The first two days demanded a 3,200-vertical climb, from Meeks Bay to Phipps Pass, from 6,200 to 9,400 feet. The kids barely noticed the altitude. The adults did.

The Desolation Wilderness (click here for permits at https://www.recreation.gov/permits/233261 ) is a 50-mile by 30-mile slab of granite left behind by the last ice age. It is graced with 100 brilliant blue lakes. It looks like a giant’s playground, with enormous boulders and huge fallen trees scattered about the landscape.

Black bears were an ever-present danger, as the area was undergoing an unprecedented “bear bloom.” Other hikers reported being harassed all night by the ursine creatures, one even invading a tent in search of food. A Cliff Bar beats clawing termites out of a dead log any day.

However, we observed the strictest of bear practices, bagging our food every night and hanging it from tall trees. It became our nightly entertainment, to see who could do the best bear bag hang. Of course, getting it down the next morning was another story.

The area had changed a lot since my grandfather brought me up to Desolation 60 years ago with a horse, a mule, a Winchester, and all the fishing gear we could carry. Then wilderness survival meant bringing in plenty of canned food and a nice 16-inch iron skillet, not the tasteless freeze-dried versions of today.

You never saw a single soul for a week. You caught your full limit of ten rainbow and brook trout as fast as you could bait the hooks. For fun, we would rummage through old log cabins outfitted with potbellied stoves for 100-year-old supplies left behind by the 19th century California gold rush. Once, we even found a crashed airplane that had been missing since the 1930s.

Nobody ever went up there.

This time around, we passed other hikers once an hour. Every lake was completely fished out. In fact, the park saw record crowds with people flocking to the safety of the great outdoors to flee the epidemic at home. Inexperienced with the outdoors, they attracted even more hungry bears.

The scouts developed a daily routine of cooking breakfast, breaking camp, hiking ten miles, searching for the ideal camping spot, setting up tents, and cooking dinner. In the process, they learned organization, self-sufficiency, responsibility, and survival skills. They don’t teach these in schools anymore.

Free time was spent playing cards for food. Winners accumulated highly sought-after beef stroganoff. The losers ended up with the despised chicken tetrazzini. I stuck to my granola bars.

On the last day, we straggled back to Meeks Bay worn, bleeding, exhausted, but exhilarated. Every morning, we woke up to a Christmas calendar view. The parents couldn’t believe we finished the entire challenging 50 miles without a major injury.

I was especially proud of my own 15- and 16-year old daughters, who are probably the first girls to ever complete a 50 miler in a Boy Scout event. The apples don’t fall far from the tree.

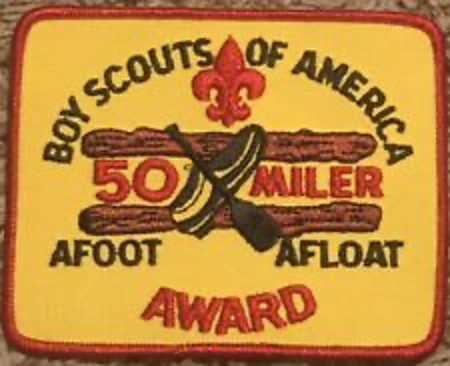

Everyone became eligible for the elite Boy Scout 50-Mile Patch, which few in the scouting movement ever achieve.

During much of the week, scouts were carping about the difficulty of the trail, the mosquitoes, and the sparse offerings of food. They fantasized about the first thing they would eat on return to civilization (banana split, pancakes with whipped cream, a Big Mac, or all three).

By the end of the week, they were talking about the next 50-mile hike. With their 2021 spring break trip to the Boy Scout Florida Sea Base cancelled, suddenly California’s Lost Coast looks very inviting.

That is, providing we can deal with the bears and the mosquitoes.