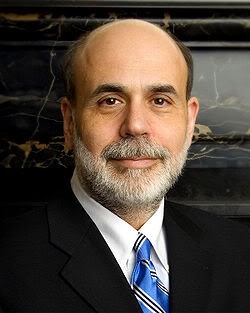

Coffee With Ben Bernanke

During 2008-2009, when the financial markets completely fell to pieces, and credit froze up, I thought, “Great, I am going to have to spend the rest of my life reliving my grandparents’ Great Depression.

One of the great policy minds of our generation, Ben Bernanke, single-handedly made sure that didn’t happen. He knew what he needed to do, was creative, and took bold action, even though he was well aware that it was diametrically opposed to his own political party’s principles.

An uproar ensued.

Now a fellow at the famed think tank, the Brooking Institution in Washington DC, Ben passed through town recently to promote his latest book out in 2022 entitled “21st Century Monetary Policy: The Federal Reserve from the Great Inflation to COVID-19.”

For eight years I watched Bernanke speak at press conferences in the most careful, restrained, cautious manner possible. After all, as the governor of America’s central bank, a mere slip of the tongue could cause panic and financial destruction. Each one was like attending a graduate class in economics. I learned from all of them.

Today, he is a completely different man. Voluble, opinionated, and even sarcastic, he let loose with one blockbuster revelation after another. It was like the dam broke, and he was making up for lost time.

Today, Bernanke counts time in terms of Federal Open Market Committee meetings (the FOMC).

He describes the week that Lehman Brothers went bankrupt as the worst panic in American history. He tried to sell it to Bank of America or Barclays Bank. But when they discovered a whopping great $70 billion hole in the balance sheet, the wheels fell off.

The bailout of insurance giant AIG was an easier sell to President George W. Bush. Although it was $85 billion in the hole, it had $1 trillion in assets, which could eventually be liquidated. They were, creating immense profits for the government.

Ben describes the TARP bank rescue package as the least popular, most successful government program in history. It was the first time the federal government took equity ownership in private banks, some 5% of the top 20.

Totally against the president’s own ideology, and voted down by his own Republican Party, it ended up generating a profit of almost $100 billion.

Oh, and it saved the global financial system too.

The key to the economic recovery was for the Fed to aggressively cut interest rates, while Europe was raising theirs. US stock markets certainly believed in it, nearly tripling off a March 2009 bottom, while the continent stagnated for six more years.

No money was ever printed during quantitative easing, contrary to popular belief. The Fed simply bought $8 trillion in bonds from the Treasury and will run them to maturity.

It’s as if they never existed. Money simply went out of one pocket into another, and the broad monetary measures were left untouched by human hands.

Ben believed he could pursue such an aggressive stance because inflationary concerns back then were “complete nonsense.”

The former Yale professor concedes that the Fed underestimated the impact of the crash. The GDP growth rate since then has been lower than he anticipated, but unemployment fell faster than thought possible, from 10.2% to 3.8% as of today.

The Fed also kept the economy from falling into the kind of liquidity trap that has mired Japan for 33 years. When prices fall, consumers hold back, knowing they can get a better deal, sapping the life out of the economy.

In the meantime, lenders are punished, as the collateral backing their debt declines as well. This is why almost all central banks are deliberately targeting a 2% inflation rate today, including ours.

Ben noted that the technologically uneducated have suffered more in this recovery than in past ones, as the rate of innovation has been so frenetic, and is accelerating thanks to AI.

This has particularly disadvantaged blue-collar workers the most, where job gains have been the weakest. Hence the recent United Auto Workers strike.

Bernanke was the smartest kid in rural Dillon, South Carolina, who, through a series of improbable accidents, and intervention by a local black civil rights leader, ended up at Harvard.

He built his career on studying the Great Depression, then the closest thing to paleontology economics had to offer, a field focused so distantly on the past that it was thought to be irrelevant.

Bernanke took over the Fed in 2006 when Greenspan was considered a rock star, inhaling his libertarian, free-market, Ayn Rand-inspired philosophy in great giant gulps.

Within a year, the economy had suddenly transported itself back to the Jurassic Age, and the landscape was suddenly overrun with T-Rex’s and Brontesauri.

He tried to stop the panic in 150 different ways, 125 of which were terrible ideas, the remaining 25 saving us from the Great Depression II.

The Fed governor is naturally a very shy and withdrawing person and would have been quite happy limiting his political career to the Princeton, New Jersey school board.

To rebuild confidence, he took his campaign to the masses, attending town hall meetings and pressing the flesh like a campaigning first-term congressman.

The price tag for Ben’s success has been large, with the Fed balance sheet exploding from $800 million to $9 trillion. The true cost of the financial crisis won’t be known for a decade or more.

Ben thinks that the biggest risk is that we grow complacent, having pulled back from the brink, and let desperately needed reforms of the financial system and the rebuilding of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac slide.

Ben Bernanke’s legacy will be defined by how well his successors do their jobs. That’s when we find out who Ben Bernanke really was.

Unwind the massive Fed balance sheet too soon, and we go back into a real depression. Too late, and hyperinflation hits. They call this “Threading the needle.”

Yikes!

Today, Bernanke sees absolutely no signs of a coming recession whatsoever. Housing has yet to seriously join the party, but will.

This is big if you are a daily player in the stock market, such as myself. He is rightfully proud of the work he did restoring the economy.

Bernanke also voiced complete confidence in his hand-picked successor, and my friend, former Berkeley professor Janet Yellen.

Ben finished our meeting with a sigh of relief, saying he was “Glad he doesn’t have to do this anymore.”

I’m happy too that we no longer need a Ben Bernanke to save our bacon. There might not be another available.