May 10, 2023

(IT’S ALL ABOUT THE DEBT CEILING)

May 10, 2023

Hello everyone,

The debt ceiling is on everyone’s mind now and is a constant topic of discussion in the financial media. So, I thought I would provide everyone with a Q & A on the issue - which I researched from several articles - to enlighten you. Enjoy.

What is the debt ceiling?

It is the total amount of money that the United States government is authorised to borrow to fulfill its financial obligations. The limit applies to almost all federal debt, including the rightly $24.6 trillion of debt held by the public and the roughly $6.8 trillion the government owes itself because of borrowing from various government accounts, like Social Security and Medicare, and trust funds. As a result, the debt continues to rise due to both annual budget deficits financed by borrowing from the public and from trust fund surpluses, which are invested in Treasury bills with the promise to be repaid later with interest.

When was the debt ceiling established?

The debt ceiling was first enacted in 1917 through the Second Liberty Bond Act and was set at $11.5 billion. In 1939, Congress created the first aggregate debt limit covering nearly all government debt and set it at $45 billion, about 10% above total debt at the time.

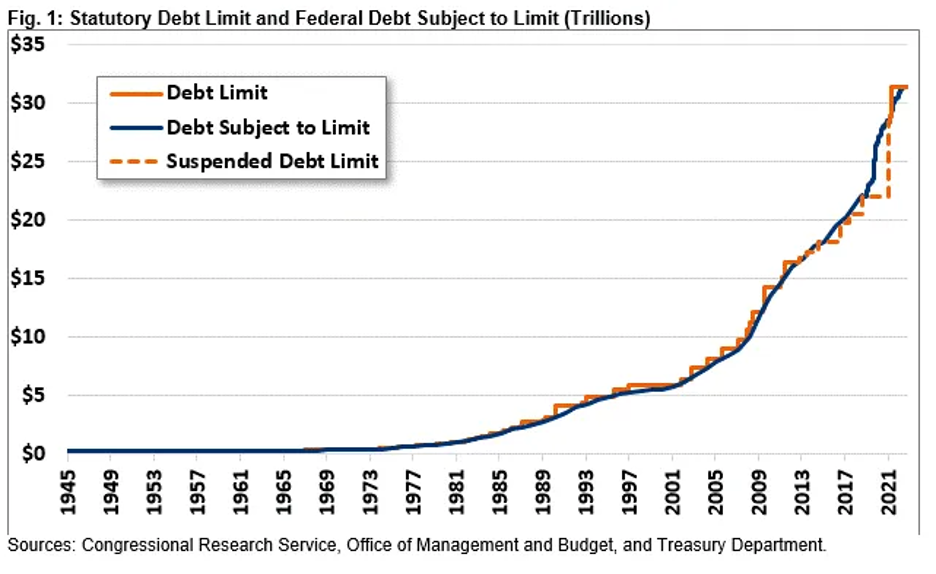

How much has the debt ceiling grown?

Since the end of World War II, Congress and the President have modified the debt ceiling more than 100 times, according to the Congressional Research Service. During the 1980s, the debt ceiling was increased from less than $1 trillion to nearly $3 trillion. Over the course of the 1990s, it was doubled to nearly $6 trillion and in the 2000s it was gain doubled to over $12 trillion. The Budget Control Act of 2011 automatically raised the debt ceiling by $900 billion and gave the President authority to increase the limit by an additional $1.2 trillion (for a total of $2.1 trillion) to $16.39 trillion. Lawmakers have suspended the debt limit, rather than raising it by a specific dollar amount, seven times since the beginning of 2013. The debt limit was increased – not suspended – twice in 2021, mostly recently in a December 2021 bill that formally increased the limit to $31.381 trillion.

What are extraordinary measures?

When the debt limit is reached, the Treasury Department both relies on cash on hand and uses a variety of accounting maneuvers, known as extraordinary measures, to avoid defaulting on the government’s obligations. For example, the Treasury has prematurely redeemed Treasury bonds held in federal employee retirement savings accounts (and replaced them later with interest), halted contributions to certain government pension funds, suspended state and local government series securities, and borrowed from one set aside to manage exchange rate fluctuations. The Treasury Department first used these measures in 1985, and there have been nine distinct “debt issuance suspension periods” since enactment of the Budget Control Act in 2011, including the current one.

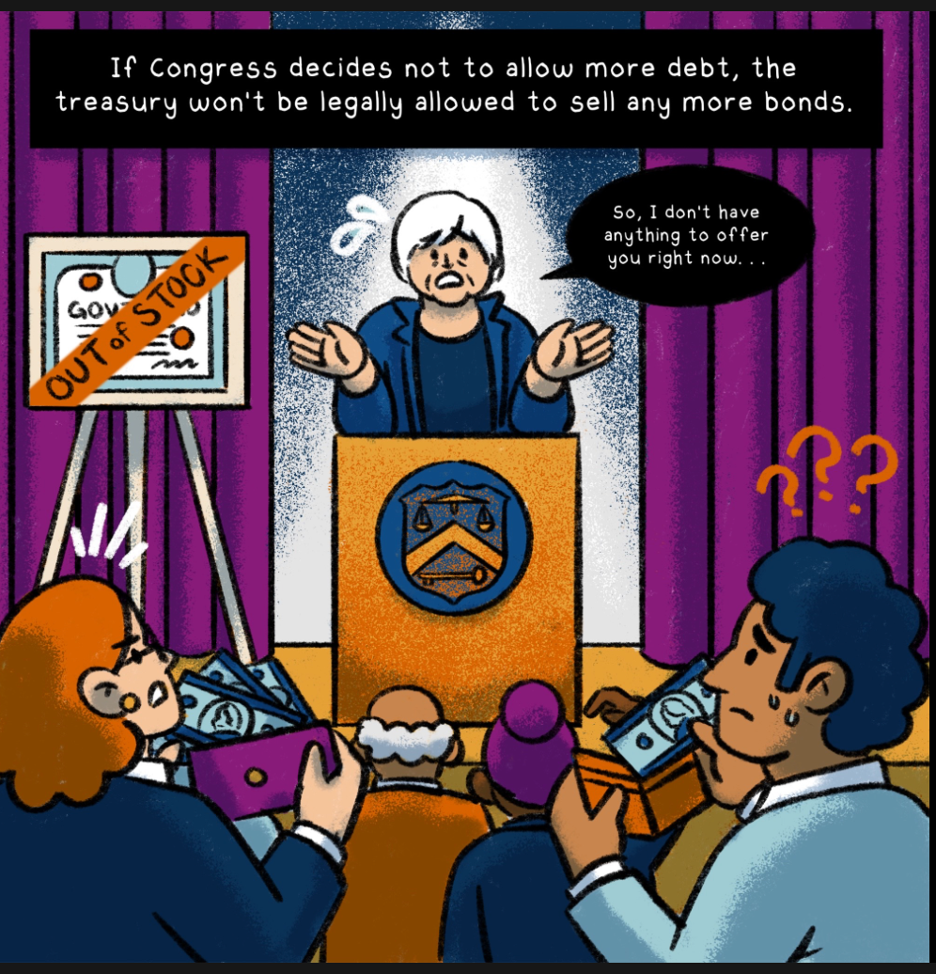

Can hitting the debt ceiling be avoided without Congressional action?

The Treasury Department’s use of extraordinary measures simply delays when the debt will reach the statutory limit. Spending more than incoming receipts has already been legally obligated; that spending will push debt beyond the ceiling. There is no plausible set of changes that could generate the instant surplus necessary to avoid having to raise or suspend the debt ceiling indefinitely.

Some believe the Treasury Department could buy more time by engaging in other unprecedented actions such as selling large amounts of gold, minting a special large-denomination coin, issuing IOUs that could be sold and traded in private markets, or invoking the Fourteenth Amendment to override the statutory debt limit. Whether any of these tools is truly available is in question, and the potential economic and political consequences of each of these options are unknown. Realistically, once extraordinary measures are exhausted, the only option to avoid defaulting on our nation’s obligations is for Congress to change the law to raise or suspend the debt ceiling.

What happens if the debt ceiling is hit?

Once the government hits the debt ceiling and exhausts all available extraordinary measures, it is no longer allowed to issue debt and soon after will run out of cash-on-hand. At that point, given annual deficits, incoming receipts would be insufficient to pay millions of daily obligations as they come due. Therefore, the federal government would have to default on many of its obligations at least temporarily, from Social Security payments and salaries for federal civilian employees and the military to veterans’ benefits and utility bills, among others.

So-called “prioritization” of payments, or making sure certain obligations among the more than 80 million that get paid per month are paid before others – such as servicing debts to bondholders before making other payments in order to avoid technical default – has been criticized as unrealistic by Treasury officials and economists. A Treasury Inspector General report from 2012 outlined scenarios that were considered during the 2011 debt ceiling run-up and found that delay of payments, which suspended all government payments until they could all be paid on a day-to-day basis, was the least harmful scenario.

How bad are the consequences of default?

A default, or even the perceived threat of one, could have serious negative economic implications. An actual default would roil global financial markets and create chaos, since both domestic and international markets depend on the relative economic and political stability of U.S. debt instruments and the U.S. economy. Interest rates would rise, and demand for Treasuries would drop as investors stop or scale back investments in Treasury securities if they are no longer considered perfectly safe. Even the threat of default during a standoff increases borrowing costs. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimatedthat the 2011 debt ceiling standoff raised borrowing costs by a total of $1.3 billion in Fiscal Year (FY) 2011, and the 2013 debt limit impasse led to additional costs over a one-year period of between $38 million and more than $70 million.

If interest rates for Treasuries increase substantially, interest rates across the economy would follow, affecting car loans, credit cards, home mortgages, business investments, and other costs of borrowing and investment. The balance sheets of banks and other institutions with large holdings of Treasuries would decline as the value of Treasuries dropped, potentially tightening the availability of credit as seen most recently in the Great Recession.

A Moody’s Analytics report released in early 2023 estimated that a default could have similar macroeconomic consequences to the Great Recession: a 4 percent Gross Domestic Product (GDP) decline, nearly 6 million lost jobs, and an unemployment rate of more than 7 percent. In addition, Moody’s predicted a $12 trillion loss in household wealth, with stocks dropping by as much as one-third at the depths of the selloff.

The White House Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) has warned that the macroeconomic effects stemming from default – or even getting too close to one – can last months or even years. A CEA report found that following the debt limit run-up in 2011, mortgage rates rose 0.7 to 0.8 percentage points for two months following the crisis and rates for auto and other consumer loans also remained elevated for months. In the event of an actual default, increased unemployment rates could persist for two to four years, the report warned.

In addition, default could also ultimately add significantly to the national debt in the form of increased borrowing costs.

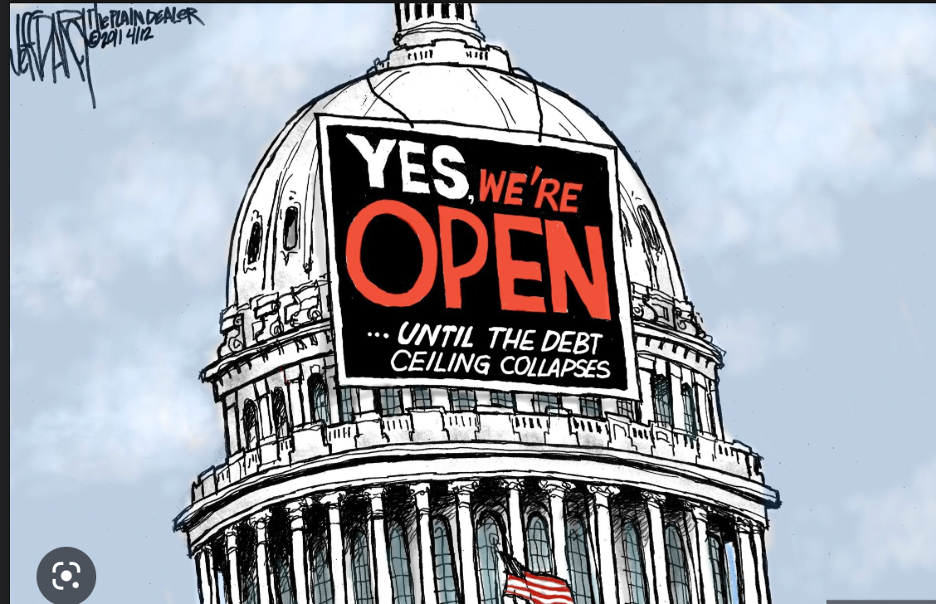

How does a shutdown differ from a default?

A shutdown occurs when Congress fails to pass appropriations bills that allow agencies to obligate new spending. As a result, the government temporarily stops paying employees and contractors who perform government services (see Q&A: Everything You Should Know About Government Shutdowns). However, many more parties are not paid in a default. A default occurs when the Treasury does not have enough cash available to pay for obligations that have already been made. In the debt ceiling context, a default would be precipitated by the government exceeding the statutory debt limit and being unable to pay all its obligations to its citizens and creditors. Without enough money to pay its bills, any of the payments are at risk, including all government spending, mandatory payments, interest on our debt, and payments to U.S. bondholders. While a government shutdown would be disruptive, a government default could be disastrous.

Have policymakers used the debt ceiling to pursue deficit reduction in the past?

Although policymakers have often enacted “clean” debt ceiling increases, Congress has also coupled increases with other legislative priorities. In several cases, Congress has attached debt ceiling increases to budget reconciliation legislation and other deficit reduction policies or processes.

Indeed, most of the major deficit reduction agreements made since 1980 have been accompanied by a debt ceiling increase, although causality has moved in both directions. On some occasions, the debt limit has been used successfully to help prompt deficit reduction, and in other cases, Congress has tacked on debt ceiling increases to deficit reduction efforts. For example, the 2011 Budget Control Act was enacted along with a debt ceiling increase, as was the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985.

In nearly all instances in which a debt limit increase was either accompanied by deficit reduction measures or included in a deficit reduction package, lawmakers have generally approved temporary increases in the debt limit to allow time for negotiations to be completed without the risk of default. For example, Congress approved a modest increase in the debt limit in December of 2009 while negotiations over statutory pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) and the establishment of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform were ongoing. Similarly, during the negotiations and consideration of the 1990 budget agreement, Congress approved six temporary increases in the debt limit before approving a long-term increase as part of the reconciliation bill implementing the deficit reduction agreement.

The Appendix contains further discussion of provisions attached to debt ceiling legislation, including bills in 1993, 1997, 2013, 2015, 2018, and 2019.

What should policymakers do?

Policymakers should work promptly to raise or suspend the debt ceiling by the deadline. Failing to raise the debt ceiling would be disastrous. It would result in severe negative consequences that experts are not capable of fully predicting in advance. Even threatening a default or taking the country to the brink of default could have serious implications. Importantly, though, failing to control the national debt would also have negative consequences; rising debt could ultimately stunt economic growth, reduce fiscal flexibility, and increase the cost burden on future generations. Thus, lawmakers should consider accompanying a debt ceiling increase with measures to begin addressing the debt.

To be sure, political advantage should not be sought by threatening default, and the debt ceiling must be raised or suspended. Lawmakers must not jeopardize the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. At the same time, the need to raise the debt ceiling can serve as a useful moment for taking stock of our fiscal state and for pursuing revenue increases, entitlement reform, and/or spending reductions.

What are the options for improving the debt ceiling?

Increasing the debt ceiling requires frequent and often contentious legislative action. While several increases have been used to enact fiscal reforms, many increases are not necessarily tied to fiscal health. For instance, debates regarding the debt ceiling often take place after the policies producing the debt have already been put in place. The debt ceiling also measures gross debt, which means that even if the budget was balanced, the debt ceiling would still have to be raised if surpluses accumulated in government trust funds like Social Security.

In The Better Budget Process Initiative: Improving the Debt Limit and subsequent publications, we have suggested reforms to the debt ceiling, grouped in four major categories:

• Linking changes in the debt limit to achieving responsible fiscal targets, so that Congress would not need to increase the debt ceiling if fiscal targets are met.

• Having debate about the debt limit when Congress is making decisions on spending and revenue levels, not after those decisions have been made.

• Applying the debt limit to more economically meaningful measures, such as debt held by the public or debt as a share of GDP.

• Replacing the debt limit with limits on future obligations.

Wishing you all a great week.

Cheers,

Jacque