Another sovereign country once appeared ready to consider Bitcoin, and for a moment, it looked like the experiment launched in Central America might quickly spread north. By 2026, however, the reality is more restrained. Bitcoin adoption has entered a slower, more selective phase across Latin America, shaped less by ideological enthusiasm and more by political limits, regulatory pressure, and hard economic trade-offs.

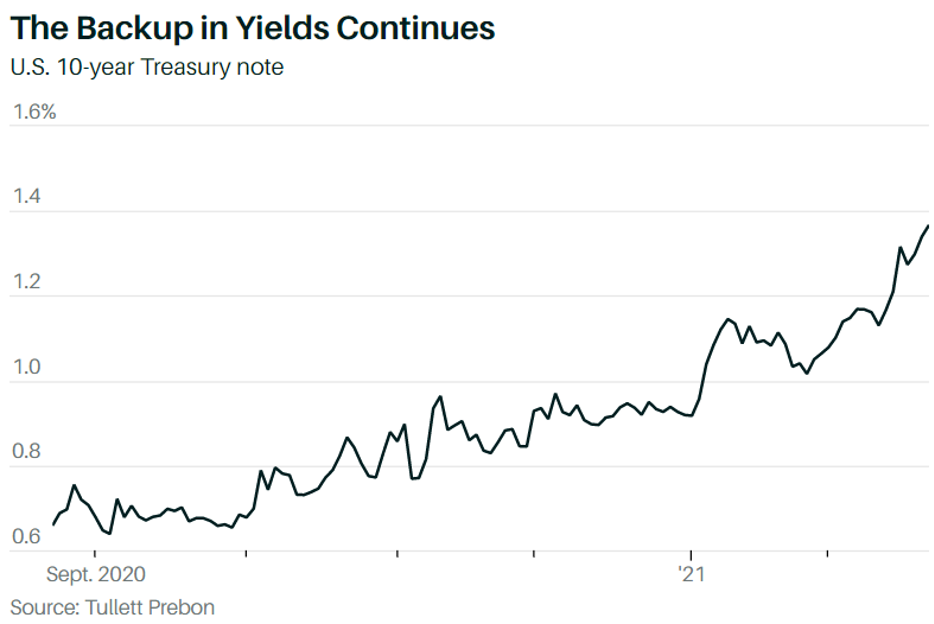

The early narrative was built on frustration with local currencies. Across parts of the region, long histories of inflation and devaluation created fertile ground for alternative monetary ideas. But broad claims of collapse have not held evenly. Mexico’s peso, for example, did not spiral into oblivion. After years of volatility, it proved comparatively resilient through the mid-2020s, supported by strong remittance inflows, nearshoring investment, and orthodox central bank policy. For most households, holding pesos in a bank did not become the nightmare scenario once implied.

That context matters when revisiting political calls to adopt Bitcoin as legal tender. Indira Kempis, a senator from Nuevo León, did publicly advocate for Bitcoin adoption and framed it as a tool for financial inclusion. She emphasized Bitcoin’s potential to serve the unbanked and said she was consulting with people knowledgeable about the asset. Those statements were real, but the effort never translated into national policy. Mexico did not move toward making Bitcoin legal tender, and no broad legislative coalition formed around the idea.

The argument that Bitcoin could bank the unbanked continues to resonate rhetorically. Millions of Mexicans remain outside the formal financial system, and digital wallets can lower barriers to entry. But by 2026, policymakers largely treat crypto as a complementary payment rail rather than a replacement for sovereign currency. Bitcoin is tolerated, regulated, and sometimes encouraged for innovation, but not elevated to the status of national money.

The experience of El Salvador has also tempered regional enthusiasm. President Nayib Bukele made history by adopting Bitcoin as legal tender, but the long-term outcome was more nuanced than early boosters expected. By 2024, El Salvador amended its Bitcoin law as part of negotiations with international lenders, removing mandatory acceptance and scaling back the legal tender framework. Bitcoin remained on the balance sheet and in official rhetoric, but its role shifted from revolutionary currency to an optional instrument.

That recalibration mattered across the region. Rather than triggering a domino effect, El Salvador’s path became a cautionary reference point. Legislators elsewhere continued to study crypto, but few were willing to stake monetary sovereignty on it.

Where Bitcoin has made steadier inroads is in payments and remittances. Crypto rails proved useful for cross-border transfers, particularly in corridors with high fees and slow settlement. Coinbase Global expanded services in Mexico by enabling recipients to cash out crypto into pesos at tens of thousands of retail locations. This targeted the remittance market directly, offering speed and cost advantages without requiring users to abandon fiat entirely.

That approach was more durable than legal-tender experiments. It allowed crypto to compete with incumbents like Western Union on efficiency rather than ideology. Over time, crypto remittances became another option in a crowded payments landscape rather than a wholesale disruption of national currencies.

Prominent business figures also continued to promote Bitcoin. Ricardo Salinas Pliego, founder and chairman of Grupo Salinas, remained one of Bitcoin’s most vocal advocates in Mexico, urging long-term holding and criticizing fiat debasement. His support kept Bitcoin in the public conversation, but it did not translate into official monetary reform.

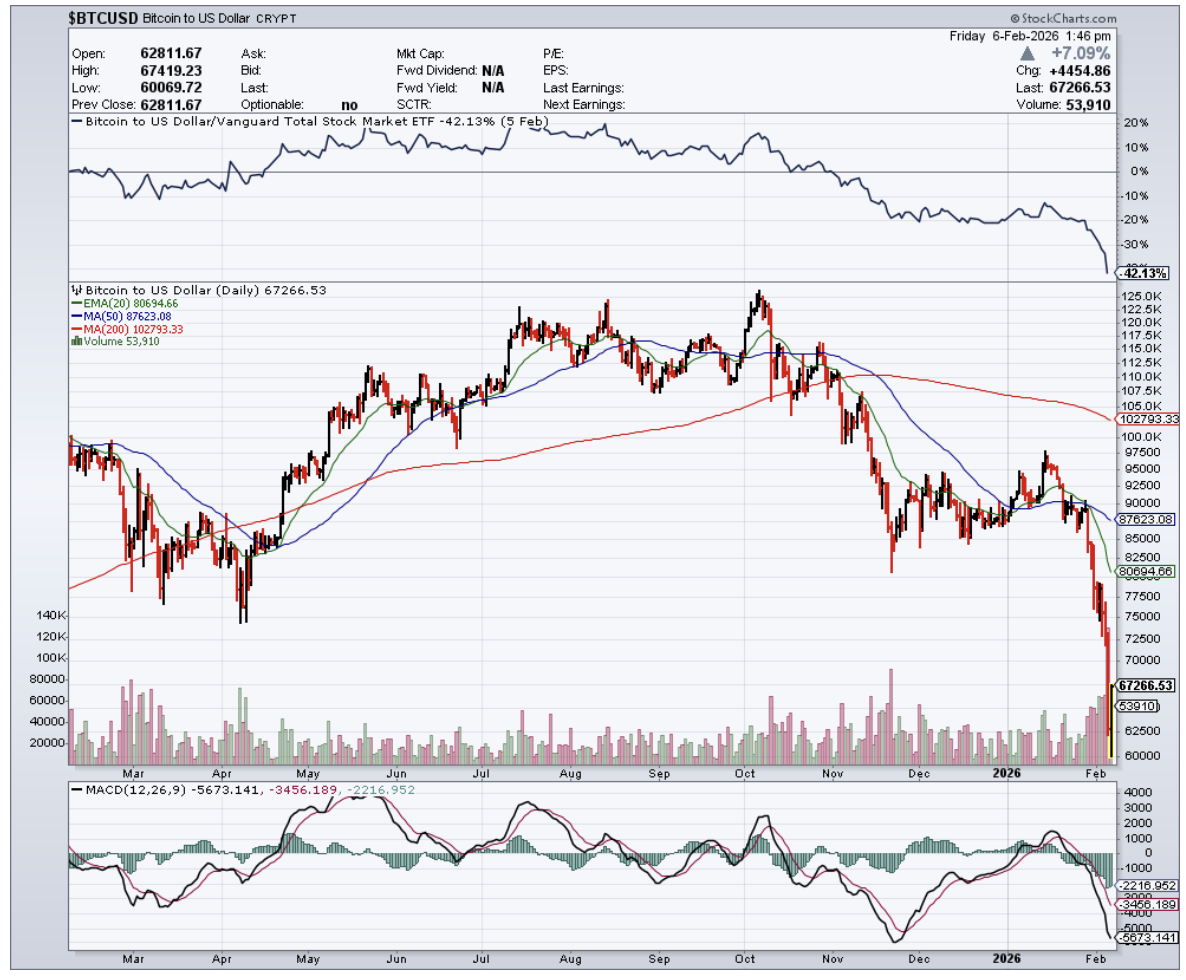

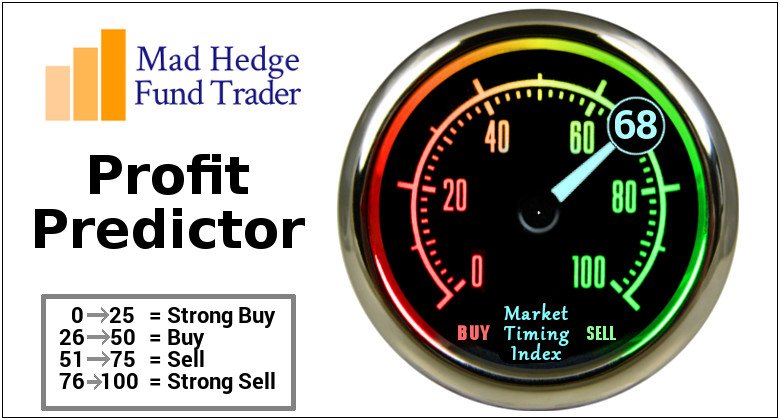

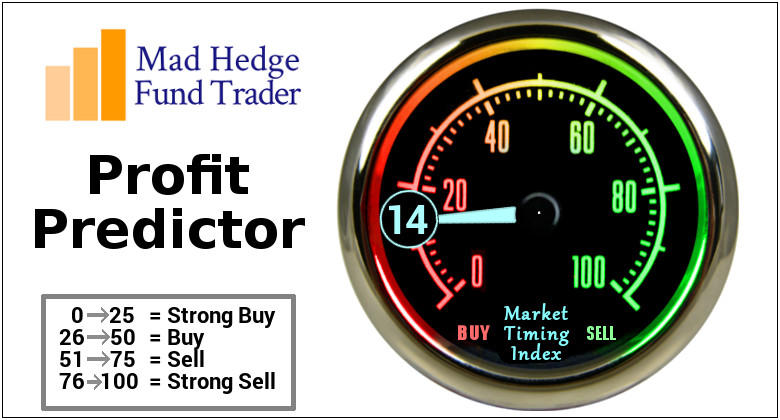

By 2026, the tone around Bitcoin in Latin America is more pragmatic. Grand predictions of immediate legal tender adoption have faded. Volatility remains, and while Bitcoin has matured relative to its early years, governments are reluctant to tie fiscal stability to an asset they do not control. The idea that entire regions would balance their budgets through Bitcoin has not materialized.

Instead, Bitcoin occupies a narrower but more realistic role: a speculative asset, a hedge for some individuals, and a payment and remittance tool where it offers clear advantages. Sovereign adoption, where it exists at all, is partial and reversible. The era of sweeping declarations has given way to incremental integration, and that slower path now defines Bitcoin’s relationship with Latin American states.