Global Market Comments

November 4, 2022

Fiat Lux

Featured Trade:

(NOVEMBER 2 BIWEEKLY STRATEGY WEBINAR Q&A),

(SPY), (LLY), (TSLA), (GOOG), (GOOGL), (JPM), (BAC), (C), (BRK), (V), (TQQQ), (CCJ), (BLK), (PHO), (GLD), (SLV), (UUP)

Global Market Comments

November 4, 2022

Fiat Lux

Featured Trade:

(NOVEMBER 2 BIWEEKLY STRATEGY WEBINAR Q&A),

(SPY), (LLY), (TSLA), (GOOG), (GOOGL), (JPM), (BAC), (C), (BRK), (V), (TQQQ), (CCJ), (BLK), (PHO), (GLD), (SLV), (UUP)

Below please find subscribers’ Q&A for the November 2 Mad Hedge Fund Trader Global Strategy Webinar broadcast from Silicon Valley in California.

Q: The country is running out of diesel fuel this month. Should I be stocking up on food?

A: No, any shortages of any fuel type are all deliberately engineered by the refiners to get higher fuel prices and will go away soon. I think there was a major effort to get energy prices up before the election. If that's the case, then look for a major decline after the election. The US has an energy glut. We are a net energy exporter. We’re supplying enormous amounts of natural gas to Europe right now, and natural gas is close to a one-year low. Shortages are not the problem, intentions are. And this is the problem with the whole energy industry, and the reason I'm not investing in it. Any moves up are short-term. And the industry's goal is to keep prices as high as possible for the next few years while demand goes to zero for their biggest selling products, like gasoline. I would be very wary about doing anything in the energy industry here, as you could get gigantic moves one way or the other with no warning.

Q Is the SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY) put spread, correct?

A: Yes, we had the November $400-$410 vertical bear put spread, which we just sold for a nice profit.

Q: I missed the LEAPS on J.P. Morgan (JPM) which has already doubled in value since last month, will we get another shot to buy?

A: Well you will get another shot to buy especially if another major selloff develops, but we’re not going down to the old October lows in the financial sector. I believe that a major long-term bull move has started in financials and other sectors, like healthcare. You won’t get the October lows, but you might get close to them.

Q: I’m waiting for a dip to get into Eli Lilly (LLY), but there are no dips.

A: Buy a little bit every day and you’ll get a nice average in a rising market. By the way, I just added Eli Lilly to my Mad Hedge long-term model portfolio, which you received on Thursday.

Q: Any thoughts about the conclusion of the Twitter deal and how it will affect tech and social media?

A: So far all of the indications are terrible. Advertisers have been canceling left and right, hate speech is up 500%, and Elon Musk personally responded to the Pelosi assassination attempt by trotting out a bunch of conspiracy theories for the sole purpose of raising traffic and not bringing light to the issue. All indications are bad, but I've been with Elon Musk on several startups in the last 25 years and they always look like they’re going bust in the beginning. It’s not even a public stock anymore and it shouldn’t be affecting Tesla (TSLA) prices either, which is still growing 50% a year, but it is.

Q: In terms of food commodities for 2023, where are prices headed?

A: Up. Not only do you have the war in Ukraine boosting wheat, soybean, and sunflower prices, but every year, global warming is going to take an increasing toll on the food supply. I know last summer when it hit 121 degrees in the Central Valley, huge amounts of crops were lost due to heat. They were literally cooked on the vine. We now have a tomato shortage and people can’t make pasta sauce because the tomatoes were all destroyed by the heat. That’s going to become an increasingly common issue in the future as temperatures rise as fast as they have been.

Q: Do I trade options in Alphabet (GOOG) or Alphabet (GOOGL)?

A: The one with the L is the holding company, the one without the L is the advertising company and the stock movements are really identical over the long term, so there really isn’t much differentiation there.

Q: Why can’t inflation be brought down by increasing the supply of all goods?

A: Because the companies won’t make them. The companies these days very carefully manage output to keep prices as high as possible. It’s not only the energy industry that does that but also all industries. So those in the manufacturing sector don’t have an interest in lowering their prices—they want high prices. If they see the prices fall, they will cut back supply.

Q: What do you think about growth plays?

A: As long as interest rates are rising, growth will lag and value will lead, and that has been clear as day for the last month. This is why we have an overwhelming value tilt to our model portfolio and our recent trade alerts. They’ve all been banks—JP Morgan (JPM), Bank of America (BAC), Citigroup (C), plus Berkshire Hathaway (BRK) and Visa (V) and virtually nothing in tech.

Q: I don’t know how to execute spread trades in options so how do I take advantage of your service?

A: Every trade alert we send out has a link to a video that shows you exactly how to do the trade. I have to admit, I’m not as young as I was when I made the videos, but they’re still valid.

Q: Is the US housing market about to crash?

A: There is a shortage of 10 million houses in the US, with the Millennials trying to buy them. If you sell your house now, you may not be able to buy another one without your mortgage going from 2.75% to 7.75%—that tends to dissuade a lot of potential selling. We also have this massive demographic wave of 85 million millennials trying to buy homes from 65 million gen x-ers. That creates a shortage of 20 million right there. That's why rents are going up at a tremendous rate, and that's why house prices have barely fallen despite the highest interest rates in 20 years.

Q: If we get good news from the Fed, should we invest in 3X ETFs such as the ProShares UltraPro QQQ (TQQQ)?

A: No, I never invest in 3X ETFs, because they are structured to screw the investor for the benefit of the issuer. These reset at the close every day, so do 2 Xs and not more. If you're not making enough money on the 2Xs, maybe you should consider another line of business.

Q: Do you think BlackRock Corporate High Yield Fund (HYT) will show the pain of slights because of their green positioning?

A: No I don’t, if anything green investing is going to accelerate as the entire economy goes green. And you’ll notice even the oil companies in their advertising are trying to paint themselves as green. They are really wolves in sheep’s clothing. They’ll never be green, but they’ll pretend to be green to cover up the fact that they just doubled the cost of gasoline.

Q: Where do you find the yield on Blackrock?

A: Just go to Yahoo Finance, type in (BLK), and it will show the yield right there under the product description. That’s recalculated by algorithms constantly, depending on the price.

Q: Do you like Cameco (CCJ)?

A: Yes, for the long term. Nuclear reactors have been given an extra five years of life worldwide thanks to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Even Japan is opening theirs.

Q: Should I short the US dollar (UUP) here?

A: The answer is definitely maybe. I would look for the dollar to try to take one more run at the highs. If that fails, we could be beginning a 10-year bear market in the dollar, and bull market in the Japanese yen, Australian dollar, British pound, and euro. This could be the next big trade.

Q: What is your outlook on Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) now?

A: I think it looks great. REITs are now commonly yielding 10%. The worst-case scenario on interest rates has been priced in—buying a REIT is essentially the same thing as buying a treasury bond, but with twice the leverage, because they have commercial credits and not government credits. We’ll be doing a lot more work on REITS. We also have tons of research on REITS from 12 years ago, the last time interest rates spiked. I'll go in and see who’s still around, and I'll be putting out some research on it.

Q: How do you see the price development of gold (GLD)?

A: Lower—the charts are saying overwhelmingly lower. Gold has no place in a rising interest rate world. At least silver (SLV) has solar panel demand.

Q: Do you have any fear of Korea going into IT?

A: Yes, they will always occupy the low end of mass manufacturing, and you can see that in the cellphone area; Samsung actually sells more phones than Apple, but they’re cheaper phones with lower-end lagging technology, and that’s the way it’s always going to be. They make practically no money on these.

Q: When can we get some more trade alerts?

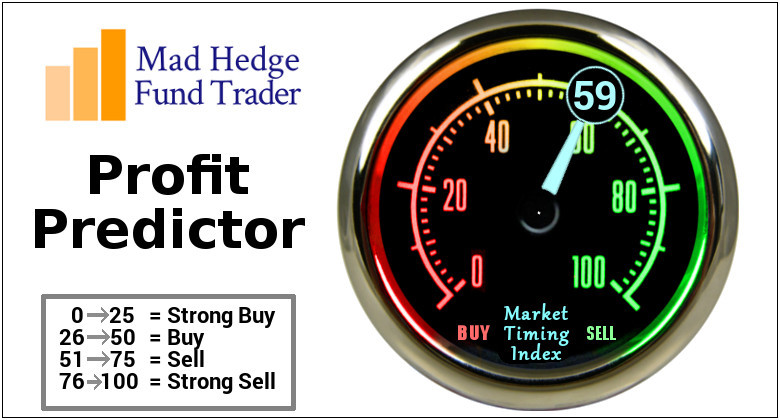

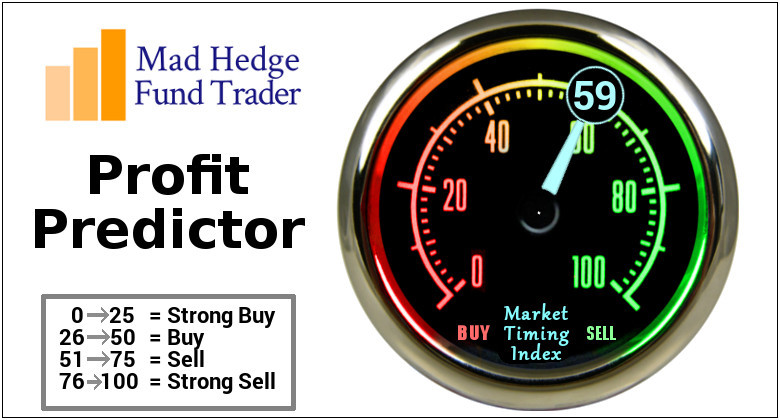

A: We are dead in the middle of my market timing index, so it says do nothing. I’m looking for either a big move down or big move up to get back into the market. This is a terrible environment to chase trades when you're trading, so I'm going to wait for the market to come to me.

Q: What about water as an investment? The Invesco Water Resources ETF (PHO)?

A: Long term I like it. There’s a chronic shortage of fresh water developing all over the world, and we, by the way, need major upgrades of a lot of water systems in the US, as we saw in Jackson, MS, and Flint, MI.

Q: Will REITs perform as well as buying rental properties over the next 10 to 20 years?

A: Yes, rental properties should do very well, as long as you’re not buying any city that has rent control. I have some rental properties in SF and dealing with rent control is a total nightmare, you’re basically waiting for your tenants to die before you raise the rent. I don’t think they have that in Nevada. But in Las Vegas, you have the other issue that is water. I think the shortage of water will start to drag on real estate prices in Las Vegas.

To watch a replay of this webinar with all the charts, bells, whistles, and classic rock music, just log on to www.madhedgefundtrader.com go to MY ACCOUNT, click on GLOBAL TRADING DISPATCH, then WEBINARS, and all the webinars from the last 12 years are there in all their glory.

Good Luck and Stay Healthy,

John Thomas

CEO & Publisher

The Diary of a Mad Hedge Fund Trader

It’s Been a Tough Market

Global Market Comments

October 31, 2022

Fiat Lux

Featured Trade:

(MARKET OUTLOOK FOR THE WEEK AHEAD, or WAS THAT THE POST-ELECTION RALLY?)

(SPY), (TLT), (VIX), (V), (MA), (AXP)

I have been through 11 bear markets in my lifetime, and I can tell you that the most ferocious rallies always take place in bear markets. This one is no exception. Short sellers always have a limited ability to take pain.

This rally took the Dow Average up 14.4% during the month of October, the biggest such monthly gain since 1976 (hmmm, just out of college and working for The Economist magazine in Tokyo, and dodging bullets in Cambodia).

The Dow outperformed NASDAQ by 9% in October, the most in 20 years. That is a pretty rare event. During the pandemic, the was a tremendous “pull forward” of technology stocks, as only commerce was possible. Now it is time for their earnings to catch up with pandemic valuations, which may take another year.

But first, let me tell you about my performance.

With some of the greatest market volatility in market history, my October month-to-date performance ballooned to +4.87%.

That leaves me with only one short in the (SPY) and 90% cash.

My 2022 year-to-date performance ballooned to +74.55%, a new high. The Dow Average is down -9.47% so far in 2022.

It is the greatest outperformance on an index since Mad Hedge Fund Trader started 14 years ago. My trailing one-year return maintains a sky-high +77.95%.

That brings my 14-year total return to +587.88%, some 2.86 times the S&P 500 (SPX) over the same period and a new all-time high. My average annualized return has ratcheted up to +45.60%, easily the highest in the industry.

And of course, there is no better indicator of the market strength than the Mad Hedge Market Timing Index, which broke above 50 for the first time in six months, all the way to 61.

It's no surprise that investors sold what was expensive (tech) and what was bought that was cheap (banks). It’s basic investing 101. Tech is still trading at a big premium to the market and double the price earnings of banks

The prospect of an end to Fed tightening has ignited a weaker dollar, prompting a stronger stock market that generated the rocket fuel for this month’s move.

All the negatives have gone, the seasonals, earnings reports, a strong dollar, and in 8 days, the election. Don’t forget that the (SPX) has delivered an eye-popping 16.3% return for every midterm election since 1961, all 15 of them.

The put/call spread is the biggest in history, about 1:4, showing that investors are piling in, or at least covering shorts, as fast as they can. Individual stock call options are trading at the biggest premiums ever.

Suffice it to say that I expected all of this, told you about it daily, and we are both mightily prospering as a result.

Much of the selling this year hasn’t been of individual stocks but of S&P 500 Index plays to hedge existing institutional portfolios. The exception is with tax loss selling to harvest losses to offset other gains. That means indiscriminate index selling begets throwing babies out with the bathwater on an industrial scale. And here is your advantage as an individual investor.

A classic example is Visa (V) which I’m’ liking more than ever right now, which I aggressively bought on the last two market downturns. The company has ample cash flow, carries no net debt, and with high inflation, is a guaranteed double-digit sales and earnings compounder.

It clears a staggering $10 trillion worth of transactions a year. With $29.3 billion in revenues in 2022 and $16 billion in net income, it has a technology-like 55% profit margin. Visa is also an aggressive buyer of its own shares, about 3% a year. That’s because it trades at a discount to other credit card processors, like Master Car (MA) and American Express (AXP).

The only negative for Visa is that it gets 55% of its earnings from aboard, which have been shrunken by the strong dollar. That is about to reverse.

It turns out that digital finance never made a dent in Visa’s prospects, as the dreadful performance of PayPal (PYPL) and Square (SQ) shares amply demonstrate.

Remember, however, that the Fed is raising interest rates by 0.75% to a 3.75%-4.00% range on Wednesday, November 2, and may do so again in December. It has been the fastest rate rise of my long and illustrious career, and also the best telegraphed.

That may give us one more dip in the stock market that will enable us to buy in on the coming Roaring Twenties.

We’ll see.

My Ten-Year View

When we come out the other side of the recession, we will be perfectly poised to launch into my new American Golden Age, or the next Roaring Twenties. With the economy decarbonizing and technology hyper-accelerating, there will be no reason not to. The Dow Average will rise by 800% to 240,000 or more in the coming decade. The America coming out the other side will be far more efficient and profitable than the old. Dow 240,000 here we come!

On Monday, October 31 at 6.45 AM, the Chicago PMI for October is released.

On Tuesday, November 1 at 7:00 AM, the JOLTS job opening report for September is out.

On Wednesday, November 2 at 8:30 AM, ADP Private Employment Report for October is published. The Fed raises interest rates at 11:00 AM and follows with a press conference at 11:30.

On Thursday, November 3 at 8:30 AM, Weekly Jobless Claims are announced.

On Friday, November 4 at 8:30 AM the Nonfarm Payroll Report for October is printed. At 2:00, the Baker Hughes Oil Rig Count is out.

As for me, during the late 1980s, the demand for Japanese bonds with attached equity warrants was absolutely exploding.

Japan was Number One, the engine of technological innovation. Everyone in the world owned a Sony Walkman. They were trouncing the United States with 45% of its car market.

The most conservative estimate for the Nikkei Average for the end of 1990 was 50,000, or up 27%. The high end was at 100,000. Why not? After all, the Nikkei had just risen tenfold in ten years and the Japanese yen had tripled in value.

In 1989, my last full year at Morgan Stanley, the Japanese warrant trading desk accounted for 80% of the firm’s total equity division profits.

The deals were coming hot and heavy. Since Morgan Stanley had the largest Japanese warrant trading operation in London, a creation of my own, we were invited to join so many deals that the firm ran out of staff to attend the signings.

Since I was the head of trading, I thought it odd that the head of investment banking wanted to speak to me. It turned out that Morgan Stanley was co-managing two monster $3 billion bond deals on the same day. Could I handle the second one? Our commission for the underwritings was $10 million for each deal!

I thought, why not, better to see how the other half lived. So, I said “yes.”

The attorneys showed up minutes later. I was given a power of attorney to sign on behalf of the entire firm and commit our capital to the underwriting $3 billion five-year bond issue for the Industrial Bank of Japan. The deal was especially attractive as the bonds carried attached put options on the Nikkei which institutional investors could buy to hedge their Japanese stock portfolios.

Since the Industrial Bank of Japan thought the stock market would never see a substantial fall, they happily sold short the put options. Only the Industrial Bank of Japan could have pulled this off as it was one of the largest and highest-rated banks in Japan. I knew the CEO well.

It turned out that there was a lot more to a deal signing than I thought, as it was done in the traditional British style. We met at the lead manager’s office in the City of London in an elegant wood-paneled private dining room filled with classic 18th century furniture.

First, there was a strong gin and tonic which you could have lit with a match. A five-course meal accompanied with a 1977 deep Pouilly Fuse white and a 1952 Bordeaux red with authority. I had my choice of elegant desserts. Sherry and a 50-year-old port followed, along with Cuban cigars, which was a problem since I had just quit smoking (my wife recently bore twins).

The British were used to these practices. Any American banker would have been left staggering, as drinking during business hours back then was illegal in New York.

Then out came the paperwork. I signed with my usual flourish and the rest of the managers followed. The Industrial Bank of Japan provided the Dom Perignon as they were about to receive $3 billion in cash the following week.

Then an unpleasant thought arose in the back of my mind. Morgan Stanley assumed the complete liability for their share of the deal. But did I just incur a massive personal liability as well?

Then I thought, naw, why pee on someone’s parade. Morgan Stanley’s been doing this for 50 years. Certainly, they knew what they were doing.

Besides, the Japanese stock market is going up forever, right? No harm, no foul. In any case, I left Morgan Stanley to start my own hedge fund a few months later.

Some seven months later, one of the greatest stock market crashes of all time began. The Nikkei fell 50% in six months and 85% in 20 years. Some 32 years later the Nikkei still hasn’t recovered its old high.

For a few years, that little voice in the back of my mind recurred. The bonds issued by the Industrial Bank of Japan fell by half in months on rocketing credit concerns. The IBJ’s naked short position in the Nikkei puts completely blew up, costing the bank $10 billion. The Bank almost went bankrupt. It was one of the worst timed deals in the history of finance. The investors were burned bigtime.

Did I ever hear about the deal I signed on again? Did process servers show up and my front door in London with a giant lawsuit? Did Scotland Yard chase me down with an arrest warrant?

Nope, nothing, nada, bupkis. I never heard a peep from anyone. It turns out you CAN lose $12 billion worth of other people’s money and face absolutely no consequences whatsoever.

Welcome to Wall Street.

Still, when the five-year maturity of the bonds passed, I breathed a sigh of relief.

My hedge fund got involved in buying Japanese equity warrants, selling short the underlying stock, thus creating massive short positions with a risk-free 40% guaranteed return. My investors loved the 1,000% profit I eventually brought in doing this.

Unlike most managers, I insisted on physical delivery of the warrant certificates, as the creditworthiness of anyone still left in the business was highly suspect. Others who took delivery used warrants to wallpaper their bathrooms (really).

They all expired worthless, I made fortunes on the short positions, and still have them by the thousands (see below).

In September 2000, the Industrial Bank of Japan, its shares down 90%, merged with the Dai-Ichi Kangyō Bank and Fuji Bank to form the Mizuho Financial Group. It was a last-ditch effort to save the Japanese financial system after ten years of recession engineered by the government.

Morgan Stanley shut down their worldwide Japanese equity warrant trading desk, losing about $20 million and laying off 200. Some staff were outright abandoned as far away as Hong Kong. Morgan Stanley was not a good firm for running large losses, as I expected.

I learned a valuable trading lesson. The greater the certainty that people have that an investment will succeed, the more likely its failure. Think of it as Chaos Theory with a turbocharger.

But we sure had a good time while the Japanese equity warrant boom lasted.

Stay Healthy,

John Thomas

CEO & Publisher

The Diary of a Mad Hedge Fund Trader

Global Market Comments

October 17, 2022

Fiat Lux

Featured Trade:

(MARKET OUTLOOK FOR THE WEEK AHEAD, or BLUNDER 3.0)

(RIVN), (TSLA), (V), (JPM), (AMAT), (HPE), (DELL), (KBH), (LEN)

There is no doubt whatsoever that the stock market tried to break down last week and failed. At worst, the Dow Average double bottomed at $29,600, the same level it reached on September 28.

And even that low was a mere 800 points lower than the one we set on June 14.

And that’s how it’s going to go.

Incremental new lows, followed by violent “rip your face off” rallies on enormous volume.

Until it ends.

That happens when markets start speculating about coming interest rate cuts sometime in 2023. And remember, you’re buying stocks for not what the economy is doing today, but for how well it will be performing in six to nine months.

You’re buying the future, not the present, or heaven forbid, the past.

That means you should use these throw-up-on-your-shoes days to scale into your favorite long-term companies. When markets inevitably rally, you can either sell for a short-term profit and rewind the video once again or keep it as part of a long-term holding.

It's a nice choice to have. I’ve been doing it all year.

With some of the greatest market volatility in market history, my October month-to-date performance ballooned to +5.00%.

I used last week’s extreme volatility to roll down strike prices for Tesla (TSLA) and JP Morgan (JPM) option spreads to manage my risk. I was still able to hang on to a 40% long position and threw out a new short in the S&P 500 at the end of Thursday.

My 2022 year-to-date performance ballooned to +75.06%, a new high. The Dow Average is down -18.48% so far in 2022. With the coming Friday options expiration, I will be up +76.49%.

It is the greatest outperformance on an index since Mad Hedge Fund Trader started 14 years ago. My trailing one-year return maintains a sky-high +78.54%.

That brings my 14-year total return to +587.62%, some 3.03 times the S&P 500 (SPX) over the same period and a new all-time high. My average annualized return has ratcheted up to +44.23%, easily the highest in the industry.

Remember that old 60/40 equity/bond investment strategy? The idea was that whenever stocks went down, the losses would be offset by the profits from rising bonds.

This year, it delivered the worst performance in 100 years, down 34.4% year-to-date. That is the inevitable end result of a decade of zero interest rates and free money that took everything up.

So what is the best strategy you could probably employ right now? A 60/40 strategy. Even I find myself checking out bond yields these days, where I got my start in life as a trader 50 years ago. Yes, before there were stocks, there were bonds. Junk is now yielding 10%. Remember, that means a holding doubles in value every six years.

The market is clearly in a mood to throw out the babies with the bathwater. I would be remiss not to mention the recent decline of Tesla posing one of its periodic tests of the faithful, now approaching a once unheard-of price earnings multiple of 30X.

Up until September 20, Elon Musk’s creation was almost immune to the bear market.

Then Twitter (TWTR) happened.

Musk agreed to take majority control of a $44 billion company, of which Elon himself is only contributing $16 billion. He sold Tesla shares last July to fund this. But the market wiped $333 billion, or 34.6%, off the market capitalization of the company. It is a wild overreaction to the move.

This has nothing to do with Tesla itself, as the richest man in the world is buying Twitter with his own pocket change. But it is undeniable that it will be a distraction of management time.

And here is all you need to know about Tesla. Tesla is the fastest growing large company in the world. Profit margins are increasing, thanks to the recent collapse of commodity prices. Unit sales will rise by 40% this year. Every time Tesla opens a new factory at a cost of $7 billion, it generates $15 billion of profit per year, forever!

Remember also, that the stock market gets an 800-pound gorilla off its back with the end of the midterm elections on November 8. It makes no difference who wins, a major uncertainty will be gone. That much IS certain.

And what happens when the Fed keeps interest rates too low for long, then raises them too much? It lowers them again too much, igniting a monster bull market in stocks. That’s also what you’re buying down here. That's what you get when you appoint a central bank governor with a political science major rather than PhDs and Nobel Prizes in Economics like the last ones.

Call it blunder 3.0.

Consumer Price Index Rockets Up to 8.6%, up 0.4% on the month and a new 40-year high. Stocks, bonds, crypto, and currencies were crushed and the US Dollar Soared. Look for new lows in stocks. Growth really took it on the nose. Expect another month of volatility until the next CPI report comes out.

Stocks Mount Historic Rally, gaining $1,420 points, or 5% of the intraday low. Stocks were down 500 in the wake of the CPI report, then up $1,420. It was mostly hedge short covering, as most institutions are too slow to react. Still, we now have a low to trade against.

The Fed Minutes are Out, and our central bank is clearly worried about doing too little than too much, when they are doing too much. At least they did six weeks, or 4,000 Dow points ago. The inflation goal is still 2.0%. Interest rates will go higher before they go lower.

Equity Inflows Hit a Record Last Week, the third highest week since 2008. Long term investors are willing to bottom fish here, even if the final bottom isn’t found for months.

Bond Liquidity Issues Haunting the Fed, and bids dry up in an endlessly falling market. The matter has been greatly exacerbated by a Fed that is now selling $95 billion a month as part of its quantitative tightening policy. It’s becoming increasingly difficult to move big blocks of bonds in a zero-bid market. Spreads are widening and size is shrinking. The bad news is that the worst is yet to come.

You Just Got an 8.7% Raise, if you are older than 61 and collecting Social Security. That is the payment increase that kicks in from January. Fortunately, some thoughtful person eons ago tied payments to the CPI, which is now going through the roof. I’m going to Hawaii with my money, even if the increase means that Social Security goes bankrupt by 2034, when I’m 82.

PC Sales Dive 19.5% in Q3, reaching only 68 million units. It’s the steepest decline since PC data collection began 30 years ago. And you wonder why they are selling the chip stocks so aggressively. High inventories are also a big problem. Lenovo was the top seller in the world at 20.2 million units, followed by Hewlett Packard’s (HPE) 17.6 million, and Dell (DELL) at 15.2 million.

Applied Materials Cuts Estimates, in line with everyone else in the industry. The new government export restrictions will cost it $250-$500 million in the current quarter. But how much is already in the price? Buy (AMAT) on dips.

Home Financing Pours into 5/1 ARMS, which can be had for a doable 5.56%. That compares to over 7.0% for the 30-year fixed, the highest since 2006. It will be low enough to keep homebuilders on life support for a couple of years Avoid (LEN) and (KBH).

REITS are Still Getting Slaughtered, with the plunge in the bond market today to multidecade lows. The REIT Index is down 30% this year, while the (SPY) is off only 21%. Real Estate Investment Trusts do best when interest rates are low. Too many investors piled into REITS in a desperate reach for yield. There’s a great trade here someday, but not yet.

My Ten-Year View

When we come out the other side of pandemic and the recession, we will be perfectly poised to launch into my new American Golden Age, or the next Roaring Twenties. With oil in a sharp decline and technology hyper-accelerating, there will be no reason not to. The Dow Average will rise by 800% to 240,000 or more in the coming decade. The America coming out the other side will be far more efficient and profitable than the old. Dow 240,000 here we come!

On Monday, October 17 at 8:30 AM, the New York Empire State Manufacturing Index for September is released.

On Tuesday, October 18 at 7:00 AM, the D for September is out.

On Wednesday, October 19 at 8:30 AM, Housing Starts and Permits for September are published.

On Thursday, October 20 at 8:30 AM, Weekly Jobless Claims are announced. At 10:00 AM, we get Existing Home Sales for September.

On Friday, October 21 at 2:00 PM, the Baker Hughes Oil Rig Count is out.

As for me, it was in 1986 when the call went out at the London office of Morgan Stanley for someone to undertake an unusual task. They needed someone who knew the Middle East well, spoke some Arabic, was comfortable in the desert, and was a good rider.

The higher-ups had obtained an impossible-to-get invitation from the Kuwaiti Royal family to take part in a camel caravan into the Dibdibah Desert. It was the social event of the year.

More importantly, the event was to be attended by the head of the Kuwait Investment Authority, who ran over $100 billion in assets. Kuwait had immense oil revenues, but almost no people, so the bulk of their oil revenues were invested in western stock markets. An investment of goodwill here could pay off big time down the road.

The problem was that the US had just launched air strikes against Libya, destroying the dictator, Muammar Gaddafi’s royal palace, our response to the bombing of a disco in West Berlin frequented by US soldiers. Terrorist attacks were imminently expected throughout Europe.

Of course, I was the only one who volunteered.

My managing director didn’t want me to go, as they couldn’t afford to lose me. I explained that in reviewing the range of risks I had taken in my life, this one didn’t even register. The following week found me in a first-class seat on Kuwait Airways headed for a Middle East in turmoil.

A limo picked me up at the Kuwait Hilton, just across the street from the US embassy, where I occupied the presidential suite. We headed west into the desert.

In an hour, I came across the most amazing sight - a collection of large tents accompanied by about 100 camels. Everyone was wearing traditional Arab dress with a ceremonial dagger. I had been riding horses all my life, camels not so much. So, I asked for the gentlest camel they had.

The camel wranglers gave me a tall female, which was more docile and obedient than the males. Imagine that! Getting on a camel is weird, as you mount them while they are sitting down. My camel had no problem lifting my 180 pounds.

They were beautiful animals, highly groomed, and in the pink of health. Some were worth millions of dollars. A handler asked me if I had ever drunk fresh camel milk, and I answered no, they didn’t offer it at Safeway. He picked up a metal bowl, cleaned it out with his hand, and milked a nearby camel.

He then handed me the bowl with a big smile across his face. There were definitely green flecks of manure floating on the top, but I drank it anyway. I had to lest my host to lose face. At least it was white. It was body temperature warm and much richer than cow’s milk.

The motion of a camel is completely different from a horse. You ride back and forth in a rocking motion. I hoped the trip was short, as this ride had repetitive motion injuries written all over it. I was using muscles I had never used before. Hit your camel with a stick and they take off at 40 miles per hour.

I learned that a camel is a super animal ideally suited for the desert. It can ride 100 miles a day, and 150 miles in emergencies, according to TE Lawrence, who made the epic 600-mile trek to Aquaba in only four weeks in the heat of summer. It can live 15 days without water, converting the fat in its hump.

In ten miles, we reached our destination. The tents went up, clouds of dust rose, the camels were corralled, and the cooking began for an epic feast that night.

It was a sight to behold. Elaborately decorated huge five wide bronze platers were brought overflowing with rice and vegetables, and every part of a sheep you can imagine, none of which was wasted. In the center was a cooked sheep’s head with the top of the skull removed so the brains were easily accessible. We all ate with our right hands.

I learned that I was the first foreigner ever invited to such an event, and the Arabs delighted in feeding me every part of the sheep, the eyes, the brains, the intestines, and gristle. I pretended to love everything, and lied back and thought of England. When they asked how it tasted, I said it was great. I lied.

As the evening progressed, the Johnny Walker Red came out of hiding. Alcohol is illegal in Kuwait, and formal events are marked by copious amounts of elaborate fruit juices. I was told that someone with a royal connection had smuggled in an entire container of whiskey and I could drink all I wanted.

The next morning I was awoken by a bellowing camel and the worst headache in the world. I threw a rock at him to get him to shut up and he sauntered over and peed all over me.

The things I did for Morgan Stanley!

Four years later, Iraq invaded Kuwait. Some of my friends were kidnapped and held for ransom, while others were never heard from again.

The Kuwaiti government said they would pay for the war if we provided the troops, tanks, and planes. So they sold their entire $100 million investment portfolio and gave the money to the US.

Morgan Stanley got the mandate to handle the liquidation, earning the biggest commission in the firm’s history. No doubt, the salesman who got the order was considered a genius, earned a promotion, and was paid a huge bonus.

I spent the year as a Marine Corps captain, flying around assorted American generals and doing the odd special opp. I got shot down and still set off airport metal detectors. No bonus here. But at least I gained insight and an experience into a medieval Bedouin lifestyle that is long gone.

They say success has many fathers. This is a classic example.

You can’t just ride out into the Kuwait desert anymore. It is still filled with mines planted by the Iraqis. There are almost no camels left in the Middle East, long ago replaced by trucks. When I was in Egypt in 2019, I rode a few mangy, pitiful animals held over for the tourists.

When I passed through my London Club last summer, the Naval and Military Club on St. James Square, who’s portrait was right at the front entrance? None other than that of Lawrence of Arabia.

It turns out we were members of the same club in more ways than one.

Stay healthy,

John Thomas

CEO & Publisher

The Diary of a Mad Hedge Fund Trader

John Thomas of Arabia

Checking Out the Local Camel Milk

This One Will Do

Traffic in Arabia

Global Market Comments

October 10, 2022

Fiat Lux

Featured Trade:

(MARKET OUTLOOK FOR THE WEEK AHEAD, or EATING YOUR SEED CORN),

(SPY), (TLT), (PANW), BRKB), (JPM), (MS), (V),

(USO), (MU), (RIVN), (TWTR), (TSLA)

You know that 10% downside risk I talked about? In other words, you may have to eat a handful of your seed corn.

We may have to eat into some of that 10% this week. With the September Consumer Price Index out on Thursday, and the big bank earnings are out Friday, there is more than a little concern about the coming trading week.

That’s why all my remaining positions are structured to handle a 10% correction or more and still expire at their maximum profit point in nine trading days.

Even in the worst-case Armageddon scenario, which we are unlikely to get, the S&P 500 is likely to fall below 3,000, or 627.90 points or 17.25% from here.

That’s what you pay me for and that’s what you are getting.

I shot out of the gate with an impressive +3.25% gain so far in October. My 2022 year-to-date performance ballooned to +72.93%, a new high. The Dow Average is down -19.3% so far in 2022 or a gob-smacking -7,000 points. It is the greatest outperformance on an index since Mad Hedge Fund Trader started 14 years ago. My trailing one-year return maintains a sky-high +81.35%.

That brings my 14-year total return to +585.49%, some 3.03 times the S&P 500 (SPX) over the same period and a new all-time high. My average annualized return has ratcheted up to +45.62%, easily the highest in the industry.

It is the greatest outperformance on an index since Mad Hedge Fund Trader started 14 years ago.

I used last week’s extreme volatility to rearrange positions, adding longs in Morgan Stanley (MS), JP Morgan (JPM), and Visa (V). That takes me to 80% long, 20% short, and 0% cash. I wisely rolled down the strikes on my Tesla position from $230-$240 to $200-$210. I covered one short in the S&P 500 (SPY). All of my options positions expire in only nine trading days.

I know that you’re probably getting boatloads of advice the sell all your stocks now, sell your house, and head for those generous 5% short term interest rates, and 8% in junk. Even I went 100% cash….in December last year. The problem is that these other gurus are giving you advice that is only a year late with perfect 20/20 hindsight.

To bail now, you risk giving up on the 100% gains in years to come. If I’m wrong, you lose 10%, if I’m right, you get a double or more. Sounds like a pretty good bet to me.

People always want to know how I pick market bottoms, something I have been doing since the Dow Average was at a miniscule $753.

The lower the market is, the less aggressive the Fed is going to be

Every single input into the Consumer Price Index is now turning down sharply, especially rents and housing costs, meaning we can expect a blockbuster decline when the next report comes out on October 13

We now have two outsiders doing the Fed’s job for it, the British economy, which is clearly collapsing, and a strong US dollar that is rapidly shrinking the foreign revenues of our multinationals, like big tech.

Capitulation indicators, occasionally spotted here and there, are now coming in volleys, the Volatility Index at $35, the (VIX) curve inversion, the RSI below 30, the ten-year US Treasury yield hit 4.0% and then instantly backed off, the British pound plunged to $1.03, and we saw absolutely massive retail selling in September.

The froth is now out of all tech stocks.

All of this brings forward the last Fed hike in interest rates and the next bull market in stocks. If the last Fed rate hike is two months away on December 14, then the reasons to sell stocks are disappearing like the last sands in an hourglass.

In my mere half century in the market, every time the CPI starts to fall, stock market “V” bottoms and begins classic “rip your face off’ rallies as the shorts panic to cover. It happened in 1970, 1974, 1980, 1990, and 2009. It will happen again in 2022. The market will smell that inflation is done, the Fed is done, and volatility becomes a distant memory.

And I hate to be so obvious, but if you sell in May, what do you do in October? You buy with both hands. Just do it on the right day. That could get you a 10% to 20% move by yearend. The S&P 500 earnings multiple has collapsed by eight points in nine months and that is too far, too fast.

How do midterm years perform? October is the best month of the year followed by November. Of the entire 16-month presidential election cycle, the coming first quarter of 2023 is the best of the entire lot.

Nonfarm Payroll Falls Short at 263.000 in September. The headline unemployment rate matched a 2022 low at 3.5%. The long-term unemployment rate, the U-6 also matched this year’s low at 6.7%. The report keeps the Fed on its current interest raising schedule. Stocks, bonds, and gold sold off 500-points.

JOLTS Drops Sharply, from an expected 11.0 million to only 10.05 million. This is the job openings report from the Department of Labor. It’s one of the sharpest declines in history. The jobs market is finally starting to deteriorate, which is just what the Fed wanted. Factory Orders for August were unchanged.

OPEC+ Cuts Quotas by 2 million, and production by 1 million, in one of the largest reductions in history. It’s an effort to maintain oil prices at current prices in the face of falling demand from a global recession. The Arabs are not your friends. It’s also a slap in the face of the anti-oil posture, pro-climate posture of the Biden administration, which responded with a further release of 10 million barrels from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. Energy stocks soar across the board. Don’t get caught standing when the music stops playing. Avoid (USO).

Why Did Russia Blow Up Their Own Pipeline? International analysts are puzzled by Putin’s latest hostile move. Is this a prelude to limited nuclear war in Ukraine? My view is that Putin expects to be deposed soon and wants to make it difficult for the next government to resume relations with Europe. Others argue that the true motivation is to enable Nordstream to file a $10 billion insurance claim. Good luck collecting on that one.

Advanced Micro Devices Bombs on weak PC sales and supply chain problems, taking the stock down 5% aftermarket. Profit margins were cut. The news could take the stock down to new lows, which didn’t really participate in this week’s monster rally. The rest of the tech sector sold off in sympathy.

Tesla Breaks Production Records in Q3, manufacturing 365,000 EVs and delivering 365,000, a record high. Sales prices have risen three times this year, while commodity costs have fallen dramatically, widening profit margins. This is the most volatile stock in the market, with one 52% correction so far this year, and another 23% correction in recent weeks. It’s the reason we just saw a “buy the rumor, sell the news” type correction that took us to the bottom of a three-month range.

Another factor is that now that big tech is rallying again, people are rotating out of Tesla, which held up well in Q3. Below here, long term Tesla bulls like my friend Ron Baron, Cathie Wood, and I start adding to big positions. With OPEC+ threatening a million barrel a day production cut, taking crude up 6%, oil alternative Tesla should be rising.

Elon Musk Pays Full Price for Twitter at $54.20 a share, completely caving on pending litigation. Wall Street consensus is that the company is worth $15 a share. It may be years before we learn what’s really going on here, leaving many scratching their heads, including me. Tesla (TSLA) plunged $15 on the news, killing off a nascent rally. The distraction of management time will be huge. Avoid (TWTR).

Rivian Raises 2025 Production Goal, from 20,000 to 25,000, after a better-than-expected 7,363 third quarter. Mass production is reaching the sweet spot for the next Tesla. The company is planning a $5 billion investment in non-union Georgia. Buy (RIVN) on dips, sell short puts and buy LEAPS.

Micron Technology to Invest $100 Billion in New York Plant. It’s all part of a retreat from China and paring war risk in Taiwan. Massive government subsidies from the Chips Act helped. Biden also expanded restrictions on the export of key semiconductor manufacturing equipment, America’s crown jewels. It means more expensive buy safer supplied chips for US industry. Buy (MU) on dips.

Hurricane Ian to Cost Insurers $63 Billion, and deaths, and the federal government may be on the hook for more. The storm double-dipped, cutting a wide swath across Florida and the Carolinas. Some 95% of the costs are carried by foreign insurers through the reinsurance market. There are too many billionaire mansions on the beach which are fully insured. This paves the way for major rate increases by insurance companies, which is why Warren Buffet loves the insurance business. Many thanks to the many foreign Mad Hedge subscribers who expressed sympathy over the storm losses.

My Ten-Year View

When we come out the other side of pandemic and the recession, we will be perfectly poised to launch into my new American Golden Age, or the next Roaring Twenties. With oil in a sharp downtrend and technology hyper-accelerating, there will be no reason not to. The Dow Average will rise by 800% to 240,000 or more in the coming decade. The America coming out the other side will be far more efficient and profitable than the old. Dow 240,000 here we come!

On Monday, October 10, no data of note is released.

On Tuesday, October 11 at 7:00 AM, the 6:00 AM, the NFIB Business Optimism Index for September is released.

On Wednesday, October 12 at 8:30 AM, Producer Price Index for September is published. At 11:00 AM, the FOMC minutes from the last Fed meeting is released.

On Thursday, October 13 at 8:30 AM, Weekly Jobless Claims are announced. We also get the blockbuster Consumer Price Index.

On Friday, October 14 at 8.30 AM, US Retail Sales for September is disclosed. At 2:00 the Baker Hughes Oil Rig Count is out.

As for me, with the 35th anniversary of the October 19, 1987 crash coming up, when shares dove 22.6% in one day, I thought I’d part with a few memories.

I was in Paris visiting Morgan Stanley’s top banking clients, who then were making a major splash in Japanese equity warrants, my particular area of expertise.

When we walked into our last appointment, I casually asked how the market was doing (Paris is six hours ahead of New York). We were told the Dow Average was down a record 300 points.

Stunned, I immediately asked for a private conference room so I could call the equity trading desk in New York to buy some stock.

A woman answered the phone, and when I said I wanted to buy, she burst into tears and threw the handset down on the floor. Redialing found all Transatlantic lines jammed.

I never bought my stock, nor found out who picked up the phone. I grabbed a taxi to Charles de Gaulle airport and flew my twin Cessna as fast as the turbocharged engines could take me back to London, breaking every known air traffic control rule.

By the time I got back, the Dow had closed down a staggering 512 points, taking the Dow average down to $1,738.74. Then I learned that George Soros asked us to bid on a $250 million blind portfolio of US stocks after the close. He said he had also solicited bids from Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch, JP Morgan, and Solomon Brothers, and would call us back if we won.

We bid 10% below the final closing prices for the lot. Ten minutes later he called us back and told us we won the auction. How much did the others bid? He told us that we were the only ones who bid at all!

Then you heard that great sucking sound. Oops!

What has never been disclosed to the public is that after the close, Morgan Stanley received a margin call from the exchange for $100 million, as volatility had gone through the roof, as did every firm on Wall Street.

We ordered JP Morgan to send the money from our account immediately. Then they lost it! After some harsh words at the top, it was found. That’s when I discovered the wonderful world of Fed wire numbers.

The next morning, the Dow continued its plunge, but after an hour managed a U-turn, and launched on a monster rally that lasted for the rest of the year. We made $75 million on that one trade from Soros.

It was the worst investment decision I have seen in the markets in 53 years, executed by its most brilliant player. Go figure. Maybe it was George’s risk control discipline kicking in?

At the end of the month, we then took a $75 million hit on our share of the British Petroleum privatization, because Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher refused to postpone the issue, believing that the banks had already made too much money.

That gave Morgan Stanley’s equity division a break-even P&L for the month of October 1987, the worst in market history. Even now, I refuse to gas up at a BP station on the very rare occasions I am driving an internal combustion engine.

Good Luck and Good Trading,

John Thomas

CEO & Publisher

The Diary of a Mad Hedge Fund Trader

Global Market Comments

September 6, 2022

Fiat Lux

Featured Trade:

(MARKET OUTLOOK FOR THE WEEK AHEAD, or WELCOME TO THE ROLLING RECESSION),

(AAPL), (NVDA), (TSLA), (USO), (BTC), (MSFT), (CRM), (V), (BA), (MSFT), (CRM), (DIS)

The airline business is booming but homebuilders are in utter despair. Hotel rooms are seeing extortionate 56% YOY price increases, while residential real estate brokers are falling flat on their faces.

It’s a recession that’s here, there, and nowhere.

Welcome to the rolling recession.

If you are lucky enough to work in a handful of in-demand industries, times have never been better. If you aren’t, then it’s Armageddon.

Look at single industries one at a time, as the media tends to do, business conditions are the worst since the Great Depression and pessimism is rampant. Look at Tesla, where there is a one-year wait to get a Model X, and there is either a modest recession on the menu, or simply slowing growth at worst.

Notice that a lot of commentators are using the word “normally”. News Flash: nothing has been normal with this economy for three years.

Which leaves us with dueling yearend forecasts for the S&P 500. It will either be at 3,900, where it is now, or 4,800. A market that is unchanged, worst case, and up 20% best case sounds like a pretty good bet to me. The prospects for individual stocks, like Tesla (TSLA), Microsoft (MSFT), or NVIDIA (NVDA) are even better, with a chance of 20% of downside or 200% of upside.

I’ll sit back and wait for the market to tell me what to do. In the meantime, I am very happy to be up 60% on the year and 90% in cash.

An interesting thing is happening to big-cap tech stocks these days. They are starting to command bigger premiums both in the main market and in other technology stocks as well.

That is because investors are willing to pay up for the “safest” stocks. In effect, they have become the new investment insurance policy. Look no further than Apple (AAPL) which, after a modest 14% decline earlier this year, managed a heroic 30% gain. Steve Jobs’ creation now boasts a hefty 28X earnings multiple. Remember when it was only 9X?

Remember, the stock sells off on major iPhone general launches like we are getting this week, so I’d be careful that my “insurance policy” doesn’t come back and bite me in the ass.

Nonfarm Payroll Report Drops to 315,000 in August, a big decline, and the Headline Unemployment Rate jumps to 3.7%. The Labor Force Participation Rate increased to 62.4%. The “discouraged worker” U-6 unemployment rate jumped to 7.0%. Manufacturing gained 22,000. Stocks loved it, but it makes a 75-basis point in September a sure thing.

Jeremy Grantham Says the Stock Super Bubble Has Yet to Burst, for the seventh consecutive year. If I listened to him, I’d be driving an Uber cab by now, commuting between side jobs at Mcdonald's and Taco Bell. Grantham sees stocks, bonds, commodities, real estate, precious metals, crypto, and collectible Beanie Babies as all overvalued. Even a broken clock is right twice a day unless you’re in the Marine Corps, which uses 24-hour clocks.

Where are the Biggest Buyers on the Dip? Microsoft (MSFT), Salesforce (CRM), and Disney (DIS), followed by Visa (V), and Boeing (BA). Analysts see 20% of upside for (MSFT), 32% for (CRM), and 21% for (DIS). Sure, some of these have already seen big moves. But the smart money is buying Cadillacs at Volkswagen prices, which I have been advocating all year. Take the Powell-induced meltdown as a gift.

The Money Supply is Collapsing, down for four consecutive months. M2 is now only up less than 1% YOY. This usually presages a sharp decline in the inflation rate. With a doubling up of Quantitative Tightening this month, we could get a real shocker of a falling inflation rate on September 13. Online job offers are fading fast and used cars have suddenly become available. This could put in this year’s final bottom for stocks.

California Heads for a Heat Emergency This Weekend, with temperatures of 115 expected. Owners are urged to fully charge their electric cars in advance and thermostats have been moved up to 78 as the electric power grid faces an onslaught of air conditioning demand. The Golden State’s sole remaining Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant has seen its life extended five years to 2030. This time, the state has a new million more storage batteries to help.

Oil (USO) Dives to New 2022 Low on spreading China lockdowns. Take the world’s largest consumer offline and it has a big impact. More lows to come.

NVIDIA (NVDA) Guides Down in the face of new US export restrictions to China. The move will cost them $400 million in revenue. These are on the company’s highest-end A100 and H100 chips which China can’t copy. (AMD) received a similar ban. It seems that China was using them for military AI purposes. The shares took a 9% dive on the news. Cathie Wood’s Ark (ARKK) Funds dove in and bought the lows.

Weekly Jobless Claims Plunge to 232,000, down from 250,000 the previous week for the third consecutive week. No recession in these numbers.

First Solar (FSLR) Increases Output by 70%, thanks to a major tax subsidy push from the Biden Climate Bill. The stock is now up 116% in six weeks. We have been following this company for a decade and regularly fly over its gigantic Nevada solar array. Buy (FSLR) on dips.

Home Prices Retreat in June to an 18% YOY gain, according to the Case Shiller National Home Price Index. That’s down from a 19.9% rate in May. Tampa (35%), Miami (33%), and Dallas (28.2%) showed the biggest gains. Blame the usual suspects.

Tesla (TSLA) Needs $400 Billion to expand its vehicle output to Musk’s 20 million units a year target. One problem: there is currently not enough commodity production in the world to do this. That sets up a bright future for every commodity play out there, except oil.

Bitcoin (BTC) is Headed Back to Cost, after breaking $20,000 on Friday. With the higher cost of electricity and mining bans, spreading the cost of making a new Bitcoin is now above $17,000. It doesn’t help that much of the new crypto infrastructure is falling to pieces.

My Ten-Year View

When we come out the other side of pandemic and the recession, we will be perfectly poised to launch into my new American Golden Age, or the next Roaring Twenties. With oil prices and inflation now rapidly declining, and technology hyper-accelerating, there will be no reason not to. The Dow Average will rise by 800% to 240,000 or more in the coming decade. The America coming out the other side will be far more efficient and profitable than the old. Dow 240,000 here we come!

With a very troublesome flip-flopping market, my August performance still posted a decent +5.13%.

My 2022 year-to-date performance ballooned to +59.96%, a new high. The Dow Average is down -13.20% so far in 2022. It is the greatest outperformance on an index since Mad Hedge Fund Trader started 14 years ago. My trailing one-year return maintains a sky-high +71.90%.

That brings my 14-year total return to +572.52%, some 2.60 times the S&P 500 (SPX) over the same period and a new all-time high. My average annualized return has ratcheted up to +44.90%, easily the highest in the industry.

We need to keep an eye on the number of US Coronavirus cases at 94.7 million, up 300,000 in a week and deaths topping 1,047,000 and have only increased by 2,000 in the past week. You can find the data here.

On Monday, September 5 markets are closed for Labor Day.

On Tuesday, September 6 at 7:00 AM, the ISM Non-Manufacturing PMI for August is out.

On Wednesday, September 7 at 11:00 AM, the Fed Beige Book for July is published.

On Thursday, September 8 at 8:30 AM, Weekly Jobless Claims are announced.

On Friday, September 9 at 2:00 the Baker Hughes Oil Rig Count is out.

As for me, the first thing I did when I received a big performance bonus from Morgan Stanley in London in 1988 was to run out and buy my own airplane.

By the early 1980s, I’d been flying for over a decade. But it was always in someone else’s plane: a friend’s, the government’s, a rental. And heaven help you if you broke it!

I researched the market endlessly, as I do with everything, and concluded that what I really needed was a six-passenger Cessna 340 pressurized twin turbo parked in Santa Barbara, CA. After all, the British pound had just enjoyed a surge again the US dollar so American planes were a bargain. It had a range of 1,448 miles and therefore was perfect for flying around Europe.

The sensible thing to do would have been to hire a professional ferry company to fly it across the pond. But what’s the fun in that? So, I decided to do it myself with a copilot I knew to keep me company. Even more challenging was that I only had three days to make the trip, as I had to be at my trading desk at Morgan Stanley on Monday morning.

The trip proved eventful from the first night. I was asleep in the back seat over Grand Junction, CO when I was suddenly awoken by the plane veering sharply left. My co-pilot had fallen asleep, running the port wing tanks dry and shutting down the engine. He used the emergency boost pump to get it restarted. I spent the rest of the night in the co-pilot’s seat trading airplane stories.

The stops at Kansas City, MO, Koshokton, OH, Bangor, ME proved uneventful. Then we refueled at Goose Bay, Labrador in Canada, held our breath and took off for our first Atlantic leg.

Flying the Atlantic in 1988 is not the same as it is today. There were no navigational aids and GPS was still top secret. There were only a handful of landing strips left over from the WWII summer ferry route, and Greenland was still littered with Mustang’s, B-17’s, B24’s, and DC-3’s. Many of these planes were later salvaged when they became immensely valuable. The weather was notorious. And a compass was useless, as we flew so close to the magnetic North Pole the needle would spin in circles.

But we did have NORAD, or America’s early warning system against a Russian missile attack.

The practice back then was to call a secret base somewhere in Northern Greenland called “Sob Story.” Why it was called that I can only guess, but I think it has something to do with a shortage of women. An Air Force technician would mark your position on the radar. Then you called him again two hours later and he gave you the heading you needed to get to Iceland. At no time did he tell you where HE was.

It was a pretty sketchy system, but it usually worked.

To keep from falling asleep, the solo pilots ferrying aircraft all chatted on frequency 123.45 MHz. Suddenly, we heard a mayday call. A female pilot had taken the backseat out of a Cessna 152 and put in a fuel bladder to make the transatlantic range. The problem was that the pump from the bladder to the main fuel tank didn’t work. With eight pilots chipping in ideas, she finally fixed it. But it was a hair-raising hour. There is no air-sea rescue in the Arctic Ocean.

I decided to play it safe and pick up extra fuel in Godthab, Greenland. Godthab has your worst nightmare of an approach, called a DME Arc. You fly a specific radial from the landing strip, keeping your distance constant. Then at an exact angle you turn sharply right and begin a descent. If you go one degree further, you crash into a 5,000-foot cliff. Needless to say, this place is fogged 365 days a year.

I executed the arc perfectly, keeping a threatening mountain on my left while landing. The clouds mercifully parted at 1,000 feet and I landed. When I climbed out of the plane to clear Danish customs (yes, it’s theirs), I noticed a metallic scraping sound. The runway was covered with aircraft parts. I looked around and there were at least a dozen crashed airplanes along the runway. I realized then that the weather here was so dire that pilots would rather crash their planes than attempt a second go.

When I took off from Godthab, I was low enough to see the many things that Greenland is famous for polar bears, walruses, and natives paddling in deerskin kayaks. It was all fascinating.

I called into Sob Story a second time for my heading, did some rapid calculations, and thought “damn”. We didn’t have enough fuel to make it to Iceland. The wind had shifted from a 70 MPH tailwind to a 70 MPH headwind, not unusual in Greenland. I slowed down the plane and configured it for maximum range.

I put out my own mayday call saying we might have to ditch, and Reykjavik Control said they would send out an orange bedecked Westland Super Lynch rescue helicopter to follow me in. I spotted it 50 miles out. I completed a five-hour flight and had 15 minutes of fuel left, kissing the ground after landing.

I went over to Air Sea rescue to thank them for a job well done and asked them what the survival rate for ditching in the North Atlantic was. They replied that even with a bright orange survival suit on, which I had, it was only about half.

Prestwick, Scotland was uneventful, just rain as usual. The hilarious thing about flying the full length of England was that when I reported my position in, the accents changed every 20 miles. I put the plane down at my home base of Leavesden and parked the Cessna next to a Mustang owned by a rock star.

I asked my pilot if ferrying planes across the Atlantic was also so exciting. He dryly answered “Yes.” He told me that in a normal year, about 10% of the planes go missing.

I raced home, changed clothes, and strode into Morgan Stanley’s office in my pin-stripped suit right on time. I didn’t say a word about what I just accomplished.

The word slowly leaked out and at lunch, the team gathered around to congratulate me and listen to some war stories.

Stay healthy,

John Thomas

CEO & Publisher

The Diary of a Mad Hedge Fund Trader

Flying the Atlantic in 1988

Looking for a Place to Land in Greenland

Landing on a Postage Stamp in Godthab, Greenland

No Such a Great Landing

No Such a Great Landing

Flying Low Across Greenland

Gassing Up in Iceland

Almost Home at Prestwick

Back to London in 1988

Legal Disclaimer

There is a very high degree of risk involved in trading. Past results are not indicative of future returns. MadHedgeFundTrader.com and all individuals affiliated with this site assume no responsibilities for your trading and investment results. The indicators, strategies, columns, articles and all other features are for educational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice. Information for futures trading observations are obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but we do not warrant its completeness or accuracy, or warrant any results from the use of the information. Your use of the trading observations is entirely at your own risk and it is your sole responsibility to evaluate the accuracy, completeness and usefulness of the information. You must assess the risk of any trade with your broker and make your own independent decisions regarding any securities mentioned herein. Affiliates of MadHedgeFundTrader.com may have a position or effect transactions in the securities described herein (or options thereon) and/or otherwise employ trading strategies that may be consistent or inconsistent with the provided strategies.