The Government's War on Cash

When I lived as a student in West Berlin during the 1960s, I had a nice little side business.

I organized weekend walking tours through the Berlin Wall at Checkpoint Charlie to visit East Berlin for American students too afraid to go alone.

To pay for it, I smuggled US dollars my customers paid me in my boots which I used to buy Ostmarks in the East at a 75% discount to the official price. I then covered lunch and all my other bills, booking a nice profit on the day.

That would be much more difficult to pull off today, as governments around the world have launched a war on cash that will not end until its ultimate demise.

The truth is governments hate cash.

This became clearly apparent when the government of India withdrew circulation of its two largest banknotes. Some 50% of Indian GDP is thought to take place in the underground economy in cash only.

The move caused a financial panic, as consumers sold gold (GLD) and other hard assets to meet bills because they were unable to settle accounts with the large denomination notes they had hoarded.

As we move towards an all-electronic economy, the few remaining purposes where cash is essential are largely illegal.

When I lived as a student in West Berlin during the 1960's, I had a nice little side business.

I organized weekend walking tours through the Berlin Wall at Checkpoint Charlie to visit East Berlin for American students too afraid to go alone.

To pay for it, I smuggled US dollars my customers paid me in my boots, which I used to buy Ostmarks in the East at a 75% discount to the official price. I then covered lunch and all my other bills, booking a nice profit on the day.

That would be much more difficult to pull off today, as governments around the world have launched a war on cash that will not end until its ultimate demise.

The truth is, governments hate cash.

This became clearly apparent when the government of India withdrew circulation of its two largest banknotes. Some 50% of Indian GDP is thought to take place in the underground economy in cash only.

The move caused a financial panic, as consumers sold gold (GLD) and other hard assets to meet bills because they were unable to settle accounts with the large denomination notes they had hoarded.

As we move towards an all-electronic economy, the few remaining purposes where cash is essential are largely illegal.

Waitresses, babysitters, and bookies don't report income to the IRS. Nor do drug dealers.

This is a big deal because eight states legalized marijuana in the last election.

Since banks are still banned from handling pot proceeds, this booming business has to take place entirely in cash. Tales about of dealers making their runs with shopping bags full of $100 bills are rampant.

The IRS estimates that $460 billion in tax revenue is lost every year through unreported income, which is largely earned in cash.

Some half of the entire US paper money supply is held by foreigners, where it is used to evade taxes, bribe foreign officials, and finance terrorism.

The US government's war on cash is not a new thing. In 1929, it cut the size of US banknotes by one third to save money on the cost of high-grade paper.

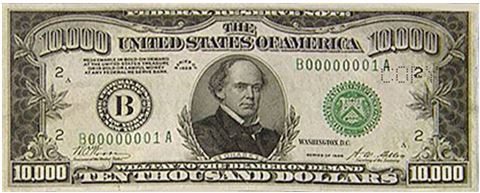

In 1970 the US Treasury banned the circulation of the $10,000, $5,000, $1,000, and $500 bills to halt mafia money laundering. Since then, the IRS has been the biggest beneficiary of the move.

Large denominations US bills are now solely the domain of collectors.

The US government would love to get out of the cash business, as it is so expensive to run. It spends about $737.4 million a year just to print American $1, $2, $5, $10, $20, $50, and $100 notes.

Paper dollar bills, which are actually made of 75% cotton and 25% linen, are completely worn out and have to be returned in only 18 months.

Coins are even a bigger loser. It costs more than two cents to make a penny.

Since the advent of color printers, counterfeiting has exploded. North Korea runs almost its entire economy on fake $100 bills, which are said to be the best in the world.

Today, some 80% of the entire $1.34 trillion M1 notes and coins in circulation in America are in the form of $100 dollar bills. That works out to $4,200 per person. Where has all that money gone?

The US is now considering eliminating even this convenient denomination. While $1 million in $100's can fit into a tote bag, that quantity of $10 bills would weigh 220 pounds, a quantity much more difficult to sneak around.

An all-electronic economy would certainly pose some privacy problems, as it would leave a massive paper trail on everything you do.

When you get audited by the IRS, the first thing they do it obtain your past three years of bank and credit card records detailing your every transaction.

State authorities will pursue phone records to establish your physical presence to verify residency. So how long did you really spend in tax-free Florida last year?

It would also pare back illegal immigration, as this is another industry that runs entirely on cash. Once here, undocumented workers are often paid in cash in restaurants and on construction sites.

There is truly no place to hide.

Other countries are already well ahead in the war of cash. In Belgium, some 93% of all financial transactions take place electronically.

Sweden has also been pushing hard on this front, taking the M1 money supply there down by 27% over the past two years.

Many small businesses there now post signs saying they don't accept cash. The goal is to move to an all-electronic economy.

The preferences of Millennials are also moving us towards the cashless economy.

Have you every been in line at Starbucks and noticed that the kid in front of you just paid $2 for a cup of coffee with his credit card? Or maybe he swiped his Apple Pay account on his iPhone?

Whatever the means, it is clear that hard cash is about to become a dinosaur.