The Mystery of the San Francisco Sublease

Commercial real estate agents are baffled. Economists are confused. Even Federal Reserve Chairman Janet Yellen is focusing a great deal of attention on the issue.

What the heck is going on with the San Francisco office subleasing market?

The question has taken on greater urgency in the wake of Friday?s abysmal nonfarm payroll report, which showed an increase of only 36,000. If no one is hiring anymore, companies certainly don?t need more office space.

When established businesses need new offices, they typically lease space in prime downtown areas. These normally take the form of a 5, 10, or 20-year lease, which the firms pay rent for on a monthly basis.

Only the wealthiest firms, like Apple (AAPL) and Oracle (ORCL) boast the cash flows that allow them the privilege of outright office ownership.

Traditionally, when companies expected the economy to slow down, they would sublease a portion of their existing space to cut costs.

When economies sped up again, they would take back their original space so they would have room to grow into.

What has analysts really scratching their heads these days is that the rate of subleasing has seen a dramatic increase in recent months. Does this mean that the economy is about to get better, worse, or neither?

Hence, the Fed?s intense interest.

I dove into the data with characteristic zeal, discovering that there is much more here than meets the eye.

It turns out that the new frenetic rate of subleasing is not an indicator of future economic activity. It is more a reflection of the structural changes besieging the US economy.

Deeper research revealed that the largest supplier of San Francisco office subleases was banker and securities broker Charles Schwab (click here for their site at https://www.schwab.com/?src=nay&sv1=dJ73RHPU_dc&sv2=73328918060&keyword=charles%20schwab&device=c&adposition=1t1&matchtype=e&network=g&devicemodel=&placement=? ).

It turns out that the entire industry is downsizing as rapidly as possible in order to cut costs. People are being replaced with machines, and machines don?t need expensive, glitzy offices on Montgomery Street, off of Union Square, or anyplace else where humans may proliferate.

Computers are much happier in giant server farms where rent and electric power are cheap, and where a small number of local techs can keep them running for pennies on the dollar.

I am thinking of The Dales, Oregon, Council Bluffs, Iowa, and Jackson County, Mississippi, where Google maintains three of its largest server farms (click here for a list of the rest at https://www.google.com/about/datacenters/inside/locations/index.html).

The shrinking of the financial industry is not only reflective of the price of office space.

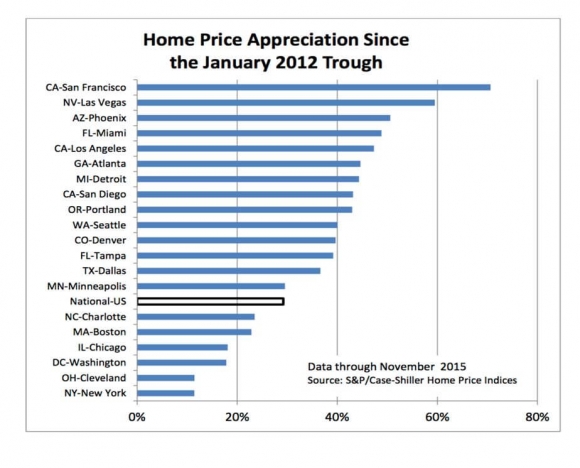

It also explains why New York City, the center of the financial industry, has shown the slowest residential price appreciation since the 2012 bottom. Layoffs there in recent years have surpassed well over 200,000.

Who has been the biggest taker of new floor space in The City by the Bay?

That would be technology companies, which are far and away the fastest growers in the economy. This should be a sign of continued health of the American economy.

Yes, it would be fair to ask the question of the risks posed by 70 or so unicorn, fast growing tech companies that have yet to go public. The bloom here is clearly off the rose, with many getting slapped with lower valuations in the latest rounds of fund raising.

But unicorns rarely occupy prime or trophy office space. They are usually just one step out of a garage, to be found in cheaper ?B? and ?C? commercial office space.

No less a giant than ride sharing giant Uber, said to be worth $65 billion, just moved into an abandoned Sears department store in downtown, low rent Oakland, CA.

As is so often the case these days, traditional, historical data can be dangerous to follow, as it may have been rendered meaningless by our hyper evolving economy.

Look before you leap.