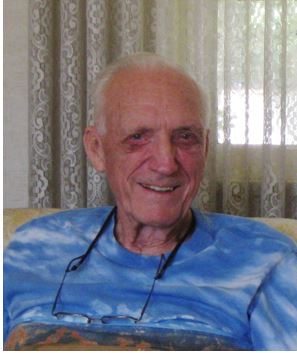

The Passing of a Great Man

It was with a heavy heart that I boarded a plane for Los Angeles a few years ago to attend a funeral for Bob, the former scoutmaster of Boy Scout Troop 108.

The event brought a convocation of ex-scouts from up and down the West coast, and said much about our age.

Bob, 85, called me two weeks before to tell me his CAT scan had just revealed advanced metastatic lung cancer. I said ?Congratulations Bob, you just made your life span.?

It was our last conversation.

He spent only a week in bed, and then was gone. As a samurai warrior might have said, it was a good death. Some thought it was the smoking he quit 20 years ago.

Others speculated that it was his close work with uranium. I chalked it up to a half century of breathing the air in Los Angeles.

Bob originally hailed from Bloomfield, New Jersey. After WWII, every East coast college was jammed with returning vets on the GI bill. So he enrolled in a small, well-regarded engineering school in New Mexico in a remote place called Alamogordo.

His first job after graduation was testing V2 rockets newly captured from the Germans at the White Sands Missile Test Range. He graduated to designing ignition systems for atomic bombs. A boom in defense spending during the fifties swept him up to the Greater Los Angeles area.

Scouts I last saw at age 13 or 14 were now 60, while the surviving dads were well into their 80?s. Everyone was in great shape, those endless miles lugging heavy packs over High Sierra passes obviously yielding lifetime benefits.

Hybrid cars lined both sides of the street. A tag along guest called out for a cigarette and a hush came over a crowd numbering over 100.

Apparently, some things stuck. It was a real cycle of life weekend. While the elders spoke about blood pressure and golf handicaps, the next generation of scouts played in the back yard, or picked lemons off a ripening tree.

Bob was the guy who taught me how to ski, cast for rainbow trout in mountain lakes, transmit Morse code, and survive in the wilderness. He used to scrawl schematic diagrams for simple radios and binary computers on a piece of paper, usually built around a single tube or transistor.

I would run off to Radio Shack to buy WWII surplus parts for pennies by the pound, and spend long nights attempting to decode impossibly fast Navy ship to ship transmissions. He was also the man who pinned an Eagle Scout badge on my uniform in front of beaming parents when I turned 15.

While in the neighborhood, I thought I would drive by the house in which I grew up, once a modest 1,800 square foot ranch style home to a happy family of nine. I was horrified to find that it had been torn down, and the majestic maple tree that I planted 40 years ago had been removed.

In its place was a giant, 6,000 square foot marble and granite monstrosity under construction for a wealthy family from China.

Profits from the enormous China-America trade have been pouring into my home town from the Middle Kingdom for the last decade, and mine was one of the last houses to go.

When I was class president of the high school here, there were 3,000 white kids, and one Chinese. Today those numbers are reversed. Such is the price of globalization.

I guess you really can?t go home again.

At the request of the family, I assisted in the liquidation of his portfolio. Bob had been an avid reader of the Diary of a Mad Hedge Fund Trader since its inception, and he had attended my Los Angeles lunches.

It seems he listened well. There was Apple (AAPL) in all its glory at a cost of $21. I laughed to myself. The master had become the student and the student had become the master.

Like I said, it was a real circle of life weekend.