The Super Bull Argument for Gold

With global stock markets in free fall and interest rates everywhere headed to zero, the outlook for gold has gone from strength to strength.

Shunned as the pariah of the financial markets for years, the yellow metal has suddenly become everyone’s favorite hedge.

Now that gold is back in fashion, how high can it really go?

The question begs your rapt attention, as the Coronavirus has suddenly unleashed a plethora of new positive fundamentals for the barbarous relic.

It turns out that gold is THE deflationary asset to own. Who knew?

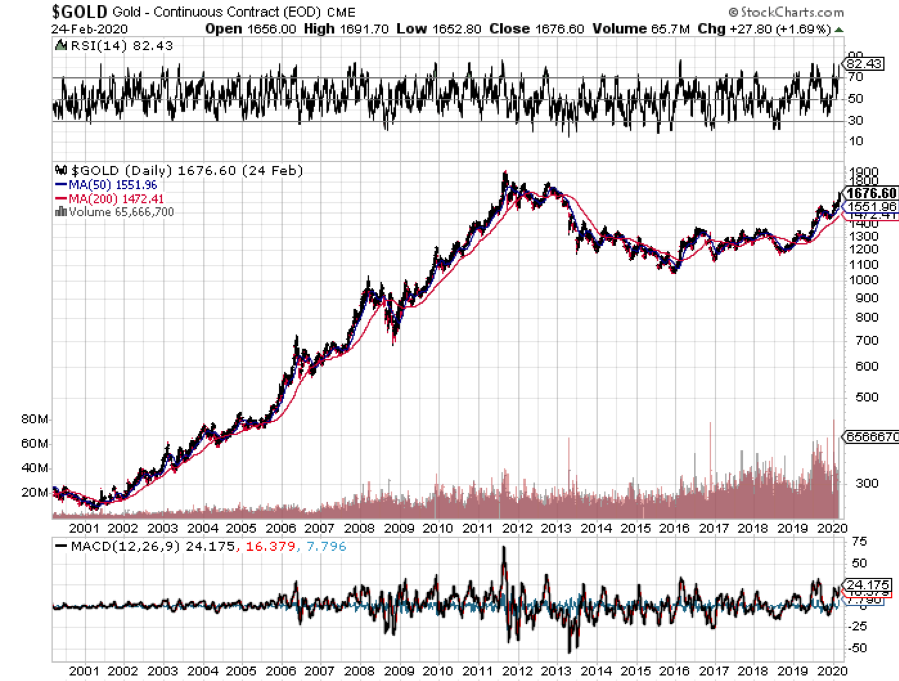

I was an unmitigated bear on the price of gold after it peaked in 2011. In recent years, the world has been obsessed with yields, chasing them down to historically low levels across all asset classes.

But now that much of the world already has, or is about to have negative interest rates, a bizarre new kind of mathematics applies to gold ownership.

Gold’s problem used to be that it yielded absolutely nothing, cost you money to store, and carried hefty transactions costs. That asset class didn’t fit anywhere in a yield-obsessed universe.

Now we have a horse of a different color.

Europeans wishing to put money in a bank have to pay for the privilege to do so. Place €1 million on deposit on an overnight account, and you will have only 996,000 Euros in a year. You just lost 40 basis points on your -0.40% negative interest rate.

With gold, you still earn zero, an extravagant return in this upside-down world. All of a sudden, zero is a win.

For the first time in human history, that gives you a 40-basis point yield advantage by gold over Euros. Similar numbers now apply to Japanese yen deposits as well.

As a result, the numbers are so compelling that it has sparked a new gold fever among hedge funds and European and Japanese individuals alike.

Websites purveying investment grade coins and bars crashed multiple times last week, due to overwhelming demand (I occasionally have the same problem). Some retailers have run out of stock.

And last week, the virus went pandemic as silver rocketed 8.6% and others like Palladium (PALL) were also frenetically bid.

So I’ll take this opportunity to review a short history of the gold market (GLD) for the young and the uninformed.

Since it last peaked in the summer of 2011 at $1,927 an ounce, the barbarous relic was beaten like the proverbial red-headed stepchild, dragging silver (SLV) down with it. It faced a perfect storm.

Gold was traditionally sought after as an inflation hedge. But with economic growth weak, wages stagnant, and much work still being outsourced abroad, deflation became rampant.

The biggest buyers of gold in the world, the Indians, have seen their purchasing power drop by half, thanks to the collapse of the rupee against the US dollar. The government increased taxes on gold in order to staunch precious capital outflows.

Chart gold against the Shanghai index, and the similarity is striking, until negative interest rates became widespread in 2016.

In the meantime, gold supply/demand balance was changing dramatically.

While no one was looking, the average price of gold production soared from $5 in 1920 to $1,400 today. Over the last 100 years, the price of producing gold has risen four times faster than the underlying metal.

It’s almost as if the gold mining industry is the only one in the world which sees real inflation, since costs soared at a 15% annual rate for the past five years.

This is a function of what I call “peak gold.” They’re not making it anymore. Miners are increasingly being driven to higher risk, more expensive parts of the world to find the stuff.

You know those tires on heavy dump trucks? They now cost $200,000 each, and buyers face a three-year waiting list to buy one.

Barrick Gold (GOLD), the world’s largest gold miner, didn’t try to mine gold at 15,000 feet in the Andes, where freezing water is a major problem, because they like the fresh air.

What this means is that when the spot price of gold fell below the cost of production, miners simply shut down their most marginal facilities, drying up supply. That has recently been happening on a large scale.

Barrick Gold, a client of the Mad Hedge Fund Trader, can still operate, as older mines carry costs that go all the way down to $600 an ounce.

No one is going to want to supply the sparkly stuff at a loss. So, supply disappeared.

I am constantly barraged with emails from gold bugs who passionately argue that their beloved metal is trading at a tiny fraction of its true value, and that the barbaric relic is really worth $5,000, $10,000, or even $50,000 an ounce (GLD).

They claim the move in the yellow metal we are seeing now is only the beginning of a 30-fold rise in prices, similar to what we saw from 1972 to 1979, when it leapt from $32 to $950.

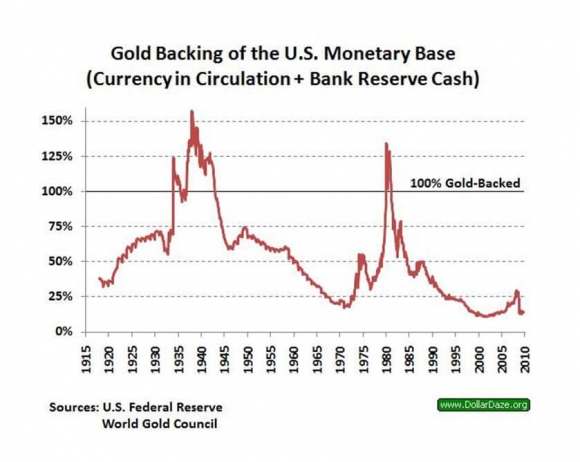

So, when the chart below popped up in my inbox showing the gold backing of the US monetary base, I felt obligated to pass it on to you to illustrate one of the intellectual arguments these people are using.

To match the gain seen since the 1936 monetary value peak of $35 an ounce, when the money supply was collapsing during the Great Depression, and the double top in 1979 when gold futures first tickled $950, this precious metal has to increase in value by 800% from the recent $1,050 low. That would take our barbarous relic friend up to $8,400 an ounce.

To match the move from the $35/ounce, 1972 low to the $950/ounce, 1979 top in absolute dollar terms, we need to see another 27.14 times move to $28,497/ounce.

Have I gotten your attention yet?

I am long term bullish on gold, other precious metals, and virtually all commodities for that matter. But I am not that bullish. These figures make my own $2,300/ounce long-term prediction positively wimp-like by comparison.

The seven-year spike up in prices we saw in the seventies, which found me in a very long line in Johannesburg, South Africa to unload my own Krugerrands in 1979, was triggered by a number of one-off events that will never be repeated.

Some 40 years of unrequited demand was unleashed when Richard Nixon took the US off the gold standard and decriminalized private ownership in 1972. Inflation then peaked around 20%. Newly enriched sellers of oil had a strong historical affinity with gold.

South Africa, the world’s largest gold producer, was then a boycotted international pariah and teetering on the edge of disaster. We are nowhere near the same geopolitical neighborhood today, and hence, my more subdued forecast.

But then again, I could be wrong.

In the end, gold may have to wait for a return of real inflation to resume its push to new highs. The previous bear market in gold lasted 18 years, from 1980 to 1998, so don’t hold your breath.

What should we look for? The surprise that your friends get out of the blue pay increase, the largest component of the inflation calculation.

This is happening now in technology and is slowly tricking down to minimum wage workers. When I visit open houses in my neighborhood in San Francisco, half the visitors are thirty-somethings wearing hoodies offering to pay cash.

It could be a long wait for real inflation, possibly into the mid-2020s, when shocking wage hikes spread elsewhere.

I’ll be back playing gold again, given a good low-risk, high-return entry point.

You’ll be the first to know when that happens.

As for the many investment advisor readers who have stayed long gold all along to hedge their clients' other risk assets, good for you.

You’re finally learning!