A Tribute to a True Veteran

Since job prospects for high school graduates in rural Pennsylvania in 1936 were poor, Mitch walked 200 miles to the nearest Marine Corp recruiting station in Baltimore.

After basic training, he spent five years rotating between duty in China and the Philippines, manning the fabled gunboats up the Yangtze River.

When WWII broke out, he was a seasoned sergeant in charge of a machine gun platoon. That put him with the seventh regiment of the First Marine division at Guadalcanal in October, 1942.

When the Japanese counterattacked, Mitch was put in charge of four Browning .30 caliber water-cooled machine guns and 33 men, dug in at trenches on a ridge above Henderson Field.

The Japanese launched massive waves of suicide attackers in a pouring tropical rainstorm all night long, frequently breaking through the line and engaging in fierce hand-to-hand combat.

If the position fell, the flank would have been broken, leading to a loss of the airfield, and possibly the entire battle. WWII would have lasted two more years.

After the first hour, all of Mitch's men were either dead or severely wounded, shot or slashed with samurai swords.

So Mitch fired one gun until it was empty, then scurried over to the next, and then the next. In between human waves, he ran back and reloaded all the guns.

To more easily pitch hand grenades, he cut the arms off his herringbone fatigues. When the Japanese launched their final assault, and then retreated, he picked up a 40-pound Browning and ran down the hill after them, firing all the way, and burning all the skin off his left forearm.

Mitch's commanding officer, Col. Herman H. Hanneken, heard the guns firing all night from the field below.

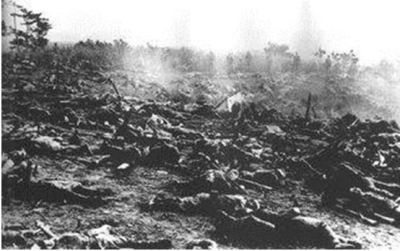

He was shocked when he visited the position the next morning, finding Mitch alone in front of a twisted sea of 1,000 Japanese bodies, not a scratch on him.

Henderson's Ridge in 1942

The iconic fictional hero in the 1949 film, Sands of Iwo Jima, Sergeant John M. Striker, was modeled after Mitch.

Tradition dictated that all military officers salute Mitch, even five star generals, and he was given a seat to attend every presidential inauguration from FDR on. Pacific countries issued stamps with his image, and Mattel sold a special GI Joe in his likeness.

When Mitch got older and infirm, I used my captain's rank to escort him on diplomatic missions overseas to attend important events, like the 40th anniversary of D-Day in Normandy.

Whenever Mitch was in town, he would join me for lunch with some of my clients with a history bent, and a more humble and self-effacing guy you never met. Mitch passed away in 2003 while he was working as a technical consultant for the pre-production of the HBO series, The Pacific. The funeral in Riverside, California was marked by an eagle continuously circling overhead which, according to the Indian shaman present, only occurs at the services for great warriors.

When I got back from the parade, I took out the samurai sword Mitch captured on that fateful day, a 1692 Muneshige, the hilt still scarred with 30-caliber slugs, and gave it a ritual polishing in sesame oil and powdered deer horn, as samurai have done for millennia.

To learn more about the First Marine Division's campaign during the war, please read the excellent paperback, The Island: A History of the First Marine Division on Guadalcanal by Herbert Laing Merillat, which you can buy from Amazon by clicking on the title.